Discretionary spending—the part of federal spending that lawmakers control through annual appropriation acts—totaled about $1.2 trillion in 2013, CBO estimates, or about 35 percent of federal outlays. Just over half of that spending was for defense programs; the rest paid for an array of nondefense activities. Some fees and other charges that are triggered by appropriation action are classified in the budget as offsetting collections and are credited against discretionary spending.

[collapsed title="…read more" class="read-more"] The discretionary budget authority (that is, the authority to incur financial obligations) provided in appropriation acts results in outlays when the money is spent. Some appropriations (such as those for employees’ salaries) are spent quickly, but others (such as those for major construction projects) are disbursed over several years. Thus, in any given year, discretionary outlays include spending both from new budget authority and from budget authority provided in earlier appropriations. [/collapsed] [collapsed]

Trends in Discretionary Spending

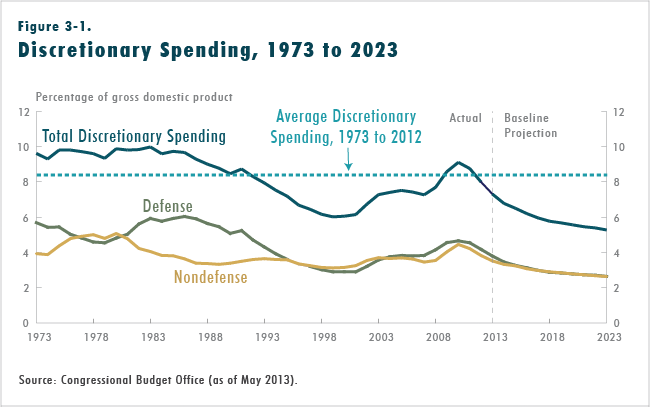

A distinct pattern in the federal budget since the 1970s has been the diminishing share of spending that occurs through the annual appropriation process. Between 1973 and 2013 discretionary spending fell from 53 percent to about 35 percent of total federal spending. Relative to the size of the economy, discretionary spending declined from 9.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1973 to a low of 6.0 percent in 1999 before rising back to about 7 percent in 2013, CBO estimates (see Figure 3-1).

Most of the decline over that period involved spending for national defense. In 1973, discretionary spending for defense was 5.7 percent of GDP. By the late 1970s, it dropped below 5.0 percent, but it rose again during the defense buildup from 1982 to 1986, when it averaged 5.9 percent. After the end of the Cold War, outlays fell relative to GDP, reaching a low of 2.9 percent at the turn of the century. Such outlays began climbing again shortly thereafter, reaching an average of 4.6 percent of GDP from 2009 through 2011. Roughly half of the growth in defense spending over the 2001–2011 period resulted from spending on operations in Iraq and Afghanistan; in 2011 such spending was equal to 1.0 percent of GDP. In 2012, discretionary spending for defense fell to 4.2 percent of GDP, and CBO estimates that it declined further in 2013.

Nondefense discretionary spending funds an array of federal activities in areas such as education, transportation, income security, veterans’ health care, and homeland security. Over the past four decades, spending in that category has generally ranged from about 3 percent to 4 percent of GDP. One exception was from 1975 to 1981, when such spending averaged almost 5 percent of GDP. Another exception was from 2009 through 2011, when funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) and from other sources associated with the federal government’s response to the 2007–2009 recession helped push nondefense outlays above 4 percent of GDP. Like defense discretionary spending, nondefense discretionary outlays as a share of GDP fell in 2012, to 3.8 percent, and CBO estimates that they declined further in 2013.

In 2012 and 2013, discretionary outlays declined not only relative to GDP but also in nominal terms. That decline stemmed largely from a waning of spending from ARRA, reduced funding for military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, and constraints imposed by the Budget Control Act of 2011. Through 2021, most discretionary appropriations will be constrained by the caps and automatic spending reductions put in place by that act; in its baseline projections for 2022 and 2023, CBO assumed that discretionary appropriations would equal the 2021 amount, with increases for projected inflation. Under that assumption, outlays from discretionary appropriations are projected to decline from about 7 percent of GDP in 2013—already below the 40-year average of 8.4 percent—to 5.3 percent in 2023. That would be the lowest amount relative to GDP at least since 1962 (the first year for which comparable data are available). Under those projections, in 2023, defense and nondefense discretionary spending would each equal 2.6 percent of GDP—the smallest share of the economy for either category in at least five decades.

Methodology Underlying Discretionary Spending Estimates

For the most part, the budgetary effects described in this chapter were calculated relative to CBO’s baseline projections, which depict paths for discretionary spending of different types over the next 10 years as directed by section 257 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985. That law states that current appropriations should be assumed to continue in later years, with adjustments to keep pace with projected inflation. (Although CBO follows that law in constructing baseline projections for individual components of discretionary spending, CBO’s baseline projections of overall discretionary spending incorporate the caps and automatic spending reductions put in place by the Budget Control Act.) The measures of inflation that CBO uses for its baseline are those specified in the law: the employment cost index for wages and salaries (applied to spending for federal personnel) and the GDP price index (for other spending).

The budgetary effects of options involving military force structure (Option 1) and acquisition (Options 4 through 9) were measured on a different basis. Because the baseline projections do not reflect programmatic details for force structure and specific weapon systems, the effects of those options are calculated relative to the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) 2014 Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). That plan includes a comprehensive outline of DoD’s intended funding requests for the 2014–2018 period that is based on the Administration’s plans for the number of military and civilian personnel, procurement and maintenance of weapon systems, and operational intensity. Through 2018, therefore, the budgetary effects considered in those options are based on DoD’s estimates of the costs of its plans. From 2019 through 2023, they are based on DoD’s estimates, if such estimates are available (for example, the Navy prepares an annual 30-year shipbuilding plan), and on CBO’s projections of price and compensation trends for the overall economy if they are not. For an option that would cancel the planned acquisition of a weapon system, for example, the potential savings reported in this volume reflect DoD’s estimates of the cost and purchasing schedule of that system, often netting out the costs to continue purchasing and operating existing systems in lieu of the system that would be canceled. The text of each acquisition option discusses the effects of the option on DoD’s ability to perform its missions—and other consequences—apart from budgetary cost.

Because the costs of implementing the FYDP would exceed CBO’s baseline projections for defense spending, the options involving military force structure and acquisition are not necessarily ways to reduce the deficits projected in CBO’s baseline. At least in part they represent options for reducing DoD’s planned spending to the amounts projected in the baseline.

In many instances, CBO would have estimated higher costs for DoD’s planned programs than the amounts budgeted either in DoD’s FYDP or in an extension of the FYDP that relies primarily on DoD’s cost estimates. However, the savings from an option relative to DoD’s budget request are better represented by the program’s costs embedded in the FYDP and its extension than by CBO’s independent cost estimates. If lawmakers enacted legislation to cancel a planned weapon system, for instance, DoD could delete the amounts budgeted for that system from its FYDP and add amounts for operating some existing systems in lieu of the canceled system in order to bring the department’s budget request closer to the funding that could be provided within the limits specified by the Budget Control Act.

Options in This Chapter

The 28 options in this chapter encompass a broad range of discretionary programs, excluding those involving health care. (Options that would affect spending for health care programs are presented in Chapter 5, as are options affecting taxes related to health.) Nine options in this chapter would affect defense programs, and the rest are for nondefense programs. Some envision broad cuts—such as Option 1, which would reduce the size of the military to meet the caps specified by the Budget Control Act, or Option 25, which would reduce federal civilian employment. Others focus on specific programs, such as Option 12, which concerns the Department of Energy’s programs for research and development in energy technologies. Some options would change the rules of eligibility for certain federal programs, such as for Pell grants (Option 20). Option 26 would impose fees to cover the cost of enforcing regulations and providing certain services.

To reduce deficits through changes in discretionary spending, lawmakers would need to reduce the statutory funding caps below the levels already established under current law or enact appropriations below those caps. The options in this chapter could be used to accomplish either of those objectives (although the savings shown for some of the defense options are measured relative to DoD’s plans rather than CBO’s baseline projections).

Alternatively, some of the options could be implemented to comply with the existing caps on discretionary funding rather than to reduce projected deficits. For example, as discussed above, savings from some of the defense options might bridge part of the gap between DoD’s plans and the existing caps. The savings from specific reductions in appropriations like those presented here also could be used to create room for an increase in appropriations for other, higher-priority purposes—while keeping total discretionary appropriations at or very close to the current statutory caps.

Overall, under the caps on budget authority established by the Budget Control Act, discretionary appropriations are projected to be $1.5 trillion lower over the 2014– 2023 period than they would be if the funding provided for 2013 was continued in later years with increases for inflation; that difference would mean an 11 percent decrease during the decade as a whole in real (inflationadjusted) outlays for a large collection of government programs and activities. The reduction in discretionary budget authority that would be accomplished by implementing all of the options presented in this chapter other than those involving military force structure or acquisition (which CBO measured relative to DoD’s plans rather than to its baseline) would account for less than half of that $1.5 trillion difference.