At a Glance

Veterans who served during the Vietnam War—including those who were deployed to combat zones and those who served elsewhere—constitute the last cohort of service members that was subject to a draft. More than 6 million of the nearly 9 million people who served on active duty during the war are still living.

The Congress and those veterans themselves have expressed concern about the lifelong effects of that military service, but little is known about their financial security now that most have left the labor force. The Congressional Budget Office compared the income of male Vietnam veterans with the income of male nonveterans the same ages. (Very few Vietnam veterans were women.) CBO found that:

- On average, Vietnam veterans in 2018 had roughly the same income as nonveterans their ages: $63,300 and $65,000, respectively. For veterans and nonveterans age 71—the modal, or most common, age of veterans—average income was also about the same.

- About 1.3 million Vietnam veterans, nearly 25 percent, collected disability compensation from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in 2018; their average annual payment was $18,100. Those payments boosted average income for all Vietnam veterans by $4,300. When those payments are excluded, veterans’ income averaged $59,000, 9 percent less than nonveterans’ income.

- The gap between the average income of veterans and nonveterans was largest for men in their mid-60s. It was smaller for older men: Veterans older than 71 had, on average, more income than nonveterans of the same age. That was true whether or not disability payments from VA were included in income.

- In general, Vietnam veterans received more money from Social Security and retirement plans than nonveterans; nonveterans had more earnings and more investment income. Those differences probably arose from differences in the types of employers and jobs that members of each group had over their working lives.

- Income was distributed more evenly among Vietnam veterans than among nonveterans. In other words, the percentages of Vietnam veterans in the highest and lowest income categories were smaller, and the percentages in the middle categories were larger, than those for nonveterans.

Notes

Notes

Unless this report indicates otherwise, all years referred to are federal fiscal years, which are designated by the calendar year in which they end. Since 1977, federal fiscal years have run from October 1 to September 30. Before 1977, federal fiscal years ran from July 1 to June 30. Years from the American Community Survey refer to calendar years.

To remove the effects of inflation, the Congressional Budget Office adjusted dollar values with the gross domestic product price index from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. All dollar values are expressed in 2018 dollars unless otherwise noted.

This report uses the terms spending and payments to refer to outlays, which are payments by the federal government to meet a legal obligation. Outlays may be made for obligations incurred in a prior fiscal year or in the current year.

Numbers in the text, tables, and figures may not add up to totals because of rounding.

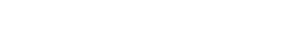

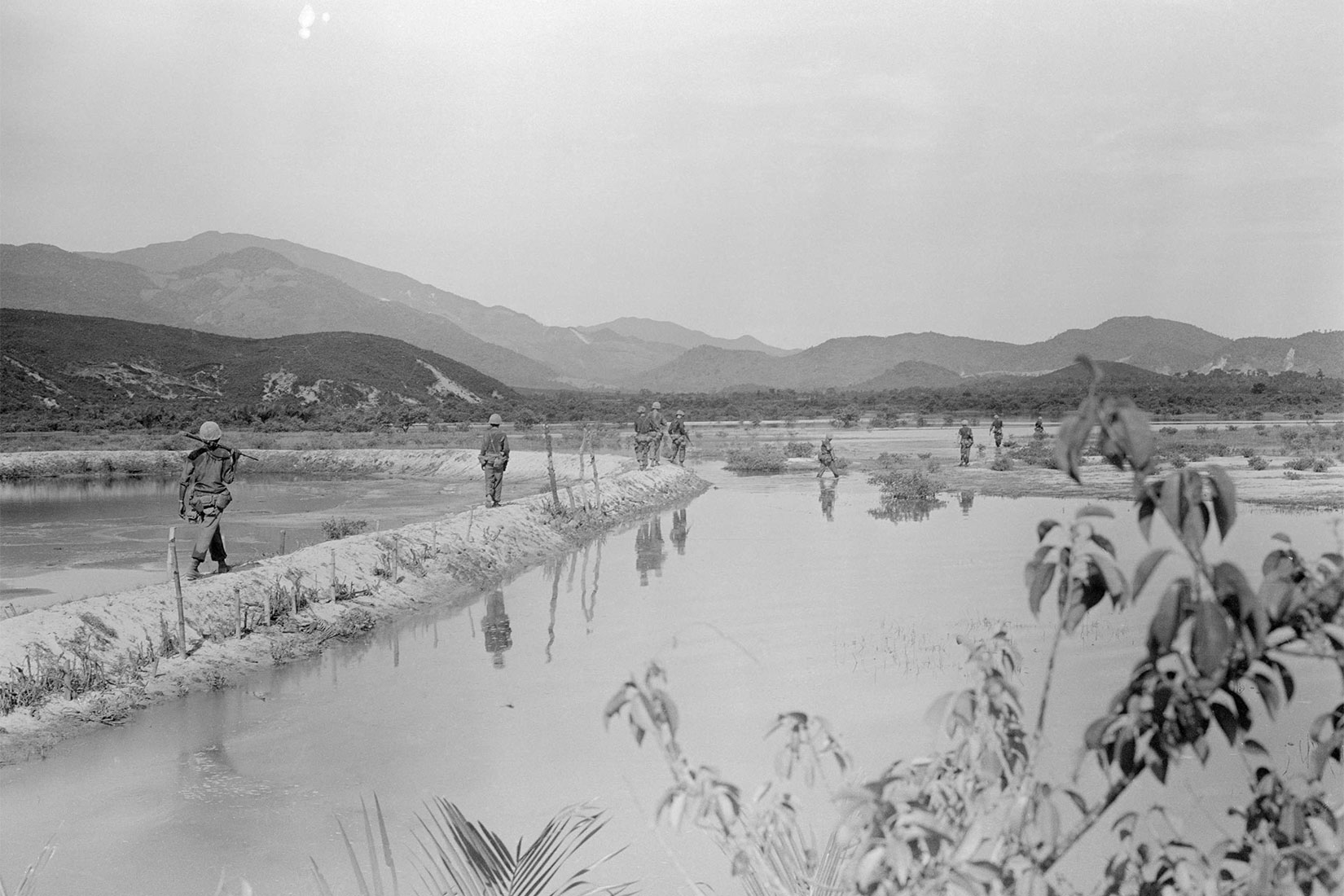

On the cover: Marines from the Third Division move along a flooded rice paddy in Chu Lai, Vietnam, on July 16, 1965. Photo courtesy of the Department of Defense.

Summary

In this report, the Congressional Budget Office looks at the income of male Vietnam veterans now that most of them have reached retirement age.1 (Very few Vietnam veterans were women.) More than 6 million of those men—some of whom were drafted and others who volunteered—are still alive. Previous research showed that veterans earned less for a decade after the war ended because of their military service but caught up to nonveterans by the early 1990s.2 But since then, as veterans have left the labor force, their sources of income have changed, including compensation and benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and little is known about veterans’ current financial status. Lawmakers and others have expressed concern about their well-being.

What Did CBO Find?

In 2018, the average income of Vietnam veterans and nonveterans was roughly comparable: For veterans, who were 63 to 78 years old at that point, it was $63,300, slightly less than the $65,000 average for nonveterans. The veterans’ average includes the disability compensation that some receive from VA. With that disability compensation excluded, veterans’ average income was $59,000, 9 percent less than nonveterans’ average income.

The income gap between veterans and nonveterans was largest for men in their mid-60s; on average, Vietnam veterans who were age 72 or older in 2018 had more income than nonveterans, whether or not VA’s disability compensation was included. For veterans and nonveterans age 71—the modal, or most common, age of veterans—there was little or no gap in average income (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Average Income of Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans at Age 71, 2018

2018 Dollars

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

The Department of Veterans Affairs provides tax-free disability compensation to veterans with medical injuries or conditions that were incurred or aggravated during active-duty military service. Other income sources may be subject to taxation.

VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Veterans age 72 or older had more income than younger veterans because those older veterans probably earned more during their working years. Older veterans generally had spent more years in the military, had higher levels of education, and probably differed in other ways that are harder to measure—such as skills learned in the military or sense of purpose. Those characteristics could affect their income in retirement.

In general (and at age 71), veterans received more income from Social Security and retirement plans than nonveterans, and nonveterans had higher earnings and more income from investments. The differences probably arose from the types of jobs veterans and nonveterans held.

With VA’s disability compensation excluded, income was distributed more equally among Vietnam veterans than among nonveterans. In comparison with nonveterans, a smaller share of veterans’ income was in either the lowest or highest quintile (fifth) of income, and a larger share was in the middle three quintiles, for all men ages 63 to 78. For veterans who received VA’s disability payments in addition to their other income, the average annual payment was $18,100. Those disability payments made their income higher than other veterans’ income, on average.

Whose Income Did CBO Examine?

CBO looked at male veterans who served on active duty during the Vietnam War and were between the ages of 63 and 78 in 2018, about 5.4 million veterans. That group included most of the veterans who served during the peak years of the war. Only those members of the National Guard and reserves who were activated during the war—roughly 25,000 men—were considered Vietnam veterans. CBO excluded women from its analysis because they were a very small share of Vietnam veterans in 2018 (4 percent). Veterans who did not serve during the Vietnam War were excluded from the samples that CBO analyzed.

Of the nearly 9 million people who served, 3.4 million were deployed to Vietnam or to other countries in Southeast Asia where the war was waged. (The rest were located in the United States or on overseas bases outside the war zone.) Less than one-quarter of those who served were drafted, but a disproportionate share of draftees served in Southeast Asia. In many aspects, the makeup of the military reflected the young male population in the United States at that time: Most service members were White and had a high school education.

How Did CBO Analyze Income?

CBO used data from the Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) to estimate income from different sources for Vietnam veterans and nonveterans ages 63 to 78. The ACS is one of the biggest surveys that the Census Bureau administers, reaching roughly 1 in 40 U.S. households each year. CBO relied on the ACS because it samples a large number of veterans, and its data on income information are about as accurate as data from other national surveys that also report veteran status.

CBO examined the selected group of veterans and nonveterans at two points in time: 2008 and 2018. In 2008, most were still working but near the end of their careers. CBO calculated earnings in that year because earnings are closely linked to retirement income. At the second point, 2018, most of the group were no longer working. CBO did not quantify the potential effects of different factors such as education and work experience that strongly influence the amount and sources of income.

At the second point in time, 2018, CBO focused on four sources of income common to veterans and nonveterans—earnings, Social Security, investments, and retirement plans. For veterans, the agency also calculated income with and without disability compensation paid by VA. In 2018, about 1.3 million Vietnam veterans ages 63 to 78 received that compensation because of medical conditions or injuries incurred during their military service. CBO’s estimates of VA’s disability payments relied on data from both the ACS and VA.

What Are the Limitations of the Report?

CBO’s study has limitations that are common to any analysis based on survey data. Some income is reported incorrectly, and CBO used statistical methods to improve the accuracy of results. In addition, the report is an incomplete picture of veterans’ overall finances because CBO did not examine all types of income. But in describing veterans’ regular sources of income in retirement, it contributes to a greater understanding of their financial security and can inform Congressional decisions about support for veterans.

The Vietnam War and the U.S. Military

Although America was involved in Vietnam for more than 10 years, the conflict itself is often considered to run from August 1964 to January 1973.3 On August 7, 1964, the Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which allowed the President “to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force” to prevent further attacks against the United States. On January 27, 1973, the Paris Peace Accords were signed, including a cease-fire and a timetable for the withdrawal of U.S. troops. Within 90 days of that agreement, U.S. ground troops had withdrawn from Vietnam. South Vietnam surrendered to North Vietnam in April 1975, and the last Americans were evacuated.

More than 8.5 million men, or about one-third of those eligible for military service, served in the U.S. armed forces during the Vietnam War.4 The first ground troops were sent to Vietnam in March 1965; their number peaked in 1968 at nearly 550,000. In total, 3.4 million men were deployed to Southeast Asia on combat tours that typically lasted for one year.

As military operations escalated, the annual number of new enlisted personnel roughly doubled in the first two years of the war (see Figure 2). In all, more than 6 million service members joined the military during the Vietnam War.

Figure 2.

Draftees and New Enlisted Personnel During the Vietnam War

Number of Personnel

Although the Department of Defense drafted civilians during the Vietnam War, draftees accounted for fewer than one-quarter of those who served.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the Department of Defense and the Selective Service System.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973. The Department of Defense estimates the number of new enlisted personnel (accessions) it will need each year to maintain specific force levels. The values shown here apply to new enlisted personnel without prior military service.

Less than 25 percent of the personnel who served during the Vietnam War were drafted; the others were volunteers. Service members generally reflected America’s young male population. In 1965 and thereafter, a majority of the armed forces were White males with high school diplomas, age 35 or younger. Men who had joined the military before the war began and served during the Vietnam conflict were likely to be more educated than the average service member and to complete a military career.

Composition and Quality of the Military

As in previous eras, men had to meet physical, moral, and mental standards to enter the military. Performance on aptitude tests and high school attainment were the two primary ways the Department of Defense (DoD) measured the quality of the enlisted force—the mental attributes that contribute to productivity and capability in the military. Aptitude tests predicted whether recruits would complete training and receive promotions in the service, and educational attainment was shown to predict later job performance.

Accessions (new enlisted personnel) were at neither the top nor the bottom of their generation in terms of measurements of ability, although the need to pass a medical examination meant that they were healthier. Fewer accessions scored among the top 10 percent on aptitude tests than young male adults generally, and the military did not accept applicants who scored in the bottom 10 percent. About 70 percent of accessions held a high school diploma or higher, compared with slightly more than 75 percent of all men ages 20 to 29.5 Accessions were likely to be more physically fit than nonveterans their age; in calendar year 1970, for instance, nearly 10 percent of potential volunteers who completed a comprehensive physical examination were disqualified for medical reasons.6

The overall quality of the enlisted forces differed depending on when they had joined the military. In 1965, about half of all active-duty personnel had already completed at least four years of service and were more likely to stay in the military for a full career (20 years) than wartime accessions. Members of the former group received more training than new enlisted personnel over their careers, had more qualifications, and probably differed in other ways as well, such as in their desire to serve in the military. For instance, in 1965, about 82 percent of all enlisted personnel (careerists and new personnel) held at least a high school diploma, higher than the average for accessions.

The officer corps was both more educated and better paid than enlisted men: All officers commissioned during the war held high school diplomas, and the vast majority had earned college degrees. However, the corps was much smaller than the enlisted force: Fewer than 500,000 officers were commissioned during the war, CBO estimates.

The Draft

About 1.9 million men were drafted during the Vietnam War, less than one-quarter of all those who served and less than one-half of accessions. Most draftees went into the Army and were deployed to Southeast Asia. The most common length of service was two years.

In the early years of the war, the draft followed the same basic system used since World War II, relying on local draft boards to select candidates. Men who registered for the draft were typically granted deferment if they had children or other dependents, were in college, or held jobs that were in the national interest. Exemptions (disqualification for medical or other reasons) were common.7 Draftees were 20 to 21 years old, on average.

As the population of young men grew in the early 1960s (because of the post-World War II baby boom), the use of deferments expanded: By 1968, one-third of men who registered for the draft received deferments, up from just 13 percent in 1958. The largest category of deferment (4.1 million) was for men with dependents, followed by those who were enrolled in college (1.8 million).8

As the war escalated, opposition to the draft intensified and concern about the fairness of deferments and exemptions increased. Educational deferments for college, in particular, were thought to favor the affluent.

A national commission in 1966 recommended replacing the existing system with a nationwide lottery, among other changes. The first lottery, in December 1969, was for men born between January 1, 1944 and December 31, 1950 (ages 19 to 25). In the early 1970s, occupational, agricultural, new-paternity, and new-student deferments were largely eliminated. Nevertheless, an individual’s chance of being drafted declined, both because draft calls decreased substantially in the 1970s and because later lotteries only considered men who would turn 20 years old in their enlistment year. In December 1972, the Selective Service System held its final lottery; on July 1, 1973, legal authority to draft men into the military expired.

Volunteers

Volunteers made up the remaining three-quarters of service members during the war. Some of those who enlisted during the war did so to avoid being drafted: Unlike draftees, volunteers could choose a service branch that might reduce their risk of being deployed (although volunteering also increased the length of an enlistment). Others joined in part because the pay and benefits were reasonable compared with civilian options. For enlisted careerists, pay was typically about 85 percent of the median pay (the midpoint value in the pay range) of White high school graduates of comparable ages for most of the war. In the 1960s, junior enlisted personnel were paid much less than most of them could have earned elsewhere, but pay raises in the early 1970s brought their income into rough parity with the private-sector wages of young high school graduates.9 Officers’ pay was consistently above the median pay of White college graduates. The military also offered additional pay to some men with special skills or who were in occupations with shortages.

Nor was income the only inducement to serve. The military offered occupational training and educational benefits. Additional benefits that were typically not found in the private sector included free medical care, low-cost groceries and merchandise from commissaries and exchanges, and on-base bowling alleys, movie theaters, and gyms. Other, less quantifiable aspects of military service—such as patriotism—also attracted volunteers.

Characteristics of Vietnam Veterans in 2018

Various characteristics—including age, education, and health—influence the type and amount of income adults have during their working years and in retirement. Vietnam veterans differed from nonveterans in several ways.

CBO examined male veterans ages 63 to 78 (mostly born between 1940 and 1955) who served during the Vietnam War, about 85 percent of the more than 6 million veterans of that era who were still alive in 2018. Veterans born before 1940 probably spent a substantial portion of their careers serving in the peacetime era before that war, and those born after 1955 would have been part of the all-volunteer force. Members of the National Guard and reserves were not considered Vietnam veterans unless they served on active duty during the war. Veterans who did not serve during the Vietnam War were excluded from the samples that CBO analyzed. Women were excluded because they composed just 4 percent of Vietnam veterans in 2018. Because the ACS does not ask whether the veterans were drafted or where they served, CBO did not incorporate those factors in its analysis.

The average Vietnam veteran was more likely than the average nonveteran to have a high school degree, to be White, to be a U.S. citizen, and to report a serious impairment in his ability to function (see Table 1). Such functional disabilities did not necessarily qualify veterans to receive disability compensation from VA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans Ages 63 to 78, 2018

Percent

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Data for Vietnam veterans were weighted to match the age distribution of nonveteran men. The median age of Vietnam veterans in 2018 was 70 and of nonveterans was 68.

a. Includes men who completed grade 12 but received no diploma.

b. Includes men who received a general equivalency diploma or alternative credential.

c. Includes anyone who reported Hispanic ancestry; the other three categories exclude that group.

d. Men were considered functionally disabled if they reported serious difficulty hearing, seeing, remembering, moving (such as walking or climbing stairs), or problems with self-care or independent living.

Age

Vietnam veterans were, on average, older than men in the same age group who did not serve. Veterans’ age distribution was bell-shaped because a large number of 18- to 23-year-olds entered military service during the height of the war (1966 to 1969). Fewer service members joined before 1965 or later in the war, so veterans in 2018 were most commonly in their late 60s and early 70s (see Figure 3). Veterans’ modal age was 71. Nearly 45 percent of all men age 71 were veterans.

In contrast to veterans’ age distribution, the distribution of nonveterans was highest at age 63 and tailed off. Through 2000, the mortality rate for all Vietnam veterans in the sample was similar to the mortality rate for nonveterans, according to the limited evidence available.10

Education

Vietnam veterans had a different pattern of educational attainment than nonveterans. Although enlisted personnel were a little less likely than nonveterans to have a high school diploma when they entered military service, by 2018 Vietnam veterans were much more likely to have completed a high school education or some college. That was partly because DoD and VA offered financial assistance to help service members and veterans further their education. For instance, more than 200,000 soldiers in the Army earned a high school diploma or its equivalent (a general educational development credential), many under the Pre-discharge Education Program.11 In addition, almost five million Vietnam veterans used the GI Bill for further education or training.12 However, a greater share of nonveterans than veterans completed a postsecondary degree (36 and 27 percent, respectively). The veterans’ share was even smaller for those younger than 72. Although some evidence shows that many men enrolled in postsecondary programs partly in an effort to avoid military service, the draft had little effect on whether they completed those programs.13

Ethnicity and Geographic Distribution

Vietnam veterans were more likely than nonveterans to be White and less likely to be Hispanic. Roughly equal percentages of veterans and nonveterans were Black. However, a slightly larger share of Black men than White men joined the enlisted ranks in the early 1970s.14 (In today’s military, the share of non-Whites who enlist is bigger than in the Vietnam era, partly because a larger share of U.S. youth are not White.) Like veterans of other eras, Vietnam veterans have tended to live and retire in the South, where large active-duty populations are located. Only a small share of all men, both Vietnam veterans and nonveterans, lived in rural communities.

Health

Vietnam veterans were more likely than nonveterans to report functional disabilities—impairments that restrict someone’s ability to work or undertake daily activities.15 Although veterans would have had to meet the military’s health and physical fitness standards, serious injuries and medical impairments may be more common among them because of intense physical training or experiences during deployment and combat. Research has confirmed that Vietnam veterans have more health problems and functional disabilities than nonveterans, including hearing loss, hepatitis C, and post-traumatic stress disorder.16 Some evidence suggests that those differences in health are increasing as the population ages. It is not certain, however, to what extent health problems are the result of military service.17

Just over 40 percent of the veterans who reported functional disabilities on the ACS received disability payments from VA, which may be awarded to veterans with a medical condition that developed or worsened during their service.18 VA determines whether veterans qualify for such service-connected disability payments and the amount of payment they receive. Service-connected disabilities are not necessarily functional disabilities—they may not substantially affect a veteran’s ability to work or perform day-to-day activities.

Compared with other men the same age in 2018, Vietnam veterans were less likely to work. In a recent study, researchers at CBO and the Urban Institute determined that older workers with little education, poor health, other income sources (besides earnings), or with health insurance were the most likely to retire early.19 Several of those categories apply to many veterans.

CBO’s Approach to Analyzing Veterans’ Income

To quantify the income of Vietnam veterans and nonveterans, CBO analyzed ACS data from 2008 and 2018.20 The ACS is among the largest of the Census Bureau’s surveys, reaching about 2 million households each year, and is designed to represent the entire U.S. population. Households in the ACS survey provide information on demographics, employment status, education, disabilities, and military service, among other topics. More than 75,000 male veterans who said they served during the Vietnam War were interviewed for the 2018 ACS.21 (CBO used the ACS’s survey weights to estimate data for all male Vietnam veterans and nonveterans.)

CBO chose the ACS after examining the Current Population Survey and the Survey of Income and Program Participation. The ACS covers more veterans than those surveys and is about as accurate, CBO concluded.

To determine VA’s disability payments, CBO analyzed administrative data from VA, partly because VA’s disability compensation is mingled with several other types of income in a residual category on the ACS.

CBO examined five sources of regular income: earnings, Social Security, retirement plans, investment income, and disability payments from VA. Onetime payments such as inheritances or home sales were excluded.22 The first four income sources CBO studied were common to all men; the fifth, disability compensation, could only be received by veterans.

- Earnings. Earnings were defined as money an employee received in the form of wages and salaries (including tips, commissions, and bonuses) and self-employment income from a business, professional practice, or farm after subtracting business expenses from gross receipts. (No distinction was made between incorporated and unincorporated businesses.)

- Social Security. ACS included retirement, disability, and survivors’ benefits, and payments made by the U.S. Railroad Retirement Board. (Railroad workers who qualify for retirement benefits do not participate in the Social Security program.)

- Investments. The category included income from assets: interest, dividends, royalties, rents, and income from estates or trusts.

- Retirement Plans. ACS defined retirement plans as pensions in the form of defined benefit and defined contribution plans from companies, unions, and federal, state, and local governments (including the military); individual retirement accounts; Keogh plans; and any other type of pension, retirement account or annuity. Pensions paid to survivors and disability pensions were included.

- Disability Compensation From VA. That compensation went to veterans with medical conditions or injuries that were incurred or aggravated during active-duty military service.

CBO did not include income from other sources reported in the ACS, such as alimony, public assistance, Supplemental Security Income, or VA’s pensions for low-income wartime veterans. Those sources accounted for less than 5 percent of total income for the men in this analysis. For instance, less than 3 percent of Vietnam veterans collected pensions from VA, according to that agency. In addition, the accuracy of reporting on those other sources of income was unclear.

CBO focused on broad trends and did not quantify the net effects of education, race, ethnicity, workforce experience, and other characteristics that exert a strong influence on the amount and sources of income people receive. Similarly, CBO did not examine other financial measures such as debt or expenses. Other studies have examined veterans’ wealth and financial well-being.23

Survey data vary from year to year, so reporting of income fluctuates annually. However, CBO conducted a sensitivity analysis that indicated the results for 2017 and 2018 did not differ substantially from each other.

Vietnam Veterans’ Earnings in 2008

To help understand Vietnam veterans’ income in retirement, CBO examined their earnings in 2008, when well over half of all men in that group were still working (as measured by the percentage who reported wage, salary, or self-employment income). Earnings before retirement are closely linked to income after exiting the labor force. For instance, employer-sponsored pensions are based on a percentage of the employee’s annual pay and the number of years worked at that employer.

In 2008, Vietnam veterans ranged in age from 53 to 68; CBO examined earnings only for men 53 to 65 because a majority of those older than 65 no longer worked. CBO looked at earnings by age because earnings can differ substantially by age. In addition, comparing veterans to nonveterans by age accounted for the disparity in the two groups’ age distribution.

Vietnam veterans earned an average of $50,000 in 2008, 20 percent less than nonveterans in the same age range, who earned an average of $62,200.24 Veterans younger than 63 earned less than nonveterans their ages, but veterans age 63 or older earned about the same. At age 61, veterans’ modal age in 2008, the difference was smaller, $6,500. Average earnings at that age were $52,600 for veterans and $59,100 for nonveterans (see Figure 4, top panel).

Figure 4.

Earnings of Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans Ages 53 to 65 and Share Who Worked, 2008

Fewer Vietnam veterans than nonveterans worked in 2008; those who did earned less, on average, than nonveterans.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Shaded area denotes the largest three-year cluster of Vietnam veterans (one-third of total). Veterans in that cluster probably served from 1966 to 1969, when forces were largest.

Earnings refer to wages, salaries, and self-employment income. Working individuals are those with nonzero earnings.

CBO did not adjust the data to account for characteristics other than age and veteran status.

When CBO looked only at men with wages, salaries, or self-employment earnings in 2008, Vietnam veterans earned, on average, $71,200, 12 percent less than nonveterans, who averaged $80,700. At age 61, veterans who worked earned 9 percent less, on average, than nonveterans.

Veterans’ earnings may have been lower than nonveterans’ earnings for several reasons: because their military experience did not fully substitute for the labor market experience it replaced; because they chose jobs with lower pay but more generous retirement benefits; because they had difficulty transitioning to civilian life; or because they had fewer job opportunities in the civilian sector, and that disadvantage might have persisted throughout their working years.

Other factors, such as employers’ preferences and legislative actions to assist veterans, surely played a part in veterans’ work history and income, although the magnitude of those effects is unknown. Employers’ views of veterans could have influenced their decisions about hiring and wages. Some employers may have believed that veterans had physical or emotional difficulties as a result of military service; others that veterans had special skills or attributes such as a sense of leadership, teamwork, or commitment. Federal legislation may have been a factor as well. Federal law prohibits discrimination in employment on the basis of past, current, or future military service.25 In addition, a law enacted in 1944 (and amended many times since) grants a hiring preference to veterans who apply for jobs in the federal government. Vietnam veterans might have had the occupational skills to fill many positions in the federal civilian workforce.

Compared with nonveterans, a markedly smaller share (5 percent smaller) of Vietnam veterans younger than 60 worked in 2008 (see Figure 4, bottom panel). The reason that a different share of Vietnam veterans and nonveterans worked is unclear. Higher rates of functional disability among those veterans may be part of the explanation, although 43 percent of veterans with those disabilities worked.26 Some researchers have suggested that disability payments from VA to some veterans allowed them to leave the labor market early.27 Among men who held jobs, about the same share of veterans (88 percent) worked full time as nonveterans (89 percent).

The sector of the economy in which workers were employed affected their retirement benefits. A larger share of Vietnam veterans (7 percent) than nonveterans (2 percent) worked for the federal government. Veterans (of all wars) made up 25 percent of the federal workforce in 2008, and 40 percent of DoD’s civilian employees. Similar shares of veterans and nonveterans worked for state or local governments (13 percent for both) and the private sector (64 percent of veterans and 63 percent of nonveterans). However, veterans were more likely than nonveterans to have blue-collar jobs in fields with a significant union presence, such as transportation and construction. In addition, fewer veterans, 16 percent, were self-employed, compared with more than 20 percent of nonveterans.

Most government workers and two-thirds of union members in the private sector had access to a traditional pension (a defined benefit plan), unlike many other workers. Those who were self-employed probably only had access to individual retirement accounts. Although it is difficult to compare the earnings of veterans and nonveterans in different sectors because of differences in jobs and employee qualifications, the types of jobs Vietnam veterans held in 2008 meant that many could expect a steady stream of income from a retirement plan.

The gap between the earnings of veterans and nonveterans, and likelihood of being employed, differed by race. Among all working men ages 53 to 65, White Vietnam veterans earned an average of $73,700, about 17 percent less than White nonveterans. The same was true to a much smaller degree for Black Vietnam veterans, who on average earned $51,200, about $2,200 (4 percent) less than Black nonveterans. Black men—whether or not they were veterans—were less likely to work than White men. For example, 72 percent of White male veterans age 61 worked, compared with 55 percent of Black male veterans that age; results were similar for White and Black nonveterans.

The earnings gap between veterans and nonveterans also differed by educational level. There was almost no difference (1 percent, or $600) between the average earnings of Vietnam veterans and nonveterans who held high school diplomas. At higher levels of education, however, earnings differed. Veterans with college degrees earned less on average (11 percent, or $13,600) than nonveterans of the same age with college degrees.

Vietnam Veterans’ Income in 2018

By 2018, most Vietnam veterans and nonveterans were no longer working. At that point, CBO measured four sources of income for men ages 63 to 78 that probably composed the vast majority of income for most men: earnings, Social Security benefits, investments, and retirement plans. For veterans, the agency also considered disability compensation from VA. That compensation, however, was paid only to certain veterans. Therefore, CBO calculated total income for veterans two ways: by averaging all five sources of income and by averaging four sources of income, excluding disability payments. CBO then compared both those measures with nonveterans’ total income.

The disability compensation VA provides is unlike other sources of income because it is only available to veterans, who may have faced special risks in the course of their military service. That compensation can be viewed as a work-related benefit, a lifetime indemnification that the federal government owes to veterans with a medical condition that was incurred or worsened while they were in the military. If those disabled veterans are out of the workforce for a long time, their Social Security benefits will be less than they otherwise would be, and they might not accumulate much personal savings. VA’s compensation mitigates such effects. The amount of that compensation can be sizable: CBO calculated that for Vietnam veterans who received it, average annual disability compensation was nearly as much as they received in Social Security benefits.

Total Income

Veterans’ average income, including disability compensation, was $63,300, whereas the average for nonveterans was $65,000. CBO found that disability compensation from VA increased veterans’ income by $4,300, on average, bringing it close to nonveterans’ income. Excluding disability income from VA, Vietnam veterans’ average income was $59,000.

Differences by Age. When including disability compensation, veterans at the modal age (71) had an average income of $65,500, $200 less than the average for all nonveterans that age ($65,700). Whether or not disability income was included in income, veterans younger than 71 had less income, on average, than nonveterans, and veterans older than 71 had more income, on average, than nonveterans (see Figure 5, top panel).

Figure 5.

Annual Income of Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans, 2018

Dollars

On average, Vietnam veterans age 71 or younger had less income than nonveterans; those age 72 or older had more income than nonveterans.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Shaded area denotes the largest three-year cluster of Vietnam veterans (one-third of total). Veterans in that cluster probably served from 1966 to 1969, when forces were largest.

Except where noted, average income is from five sources: earnings (wages, salaries, and self-employment); Social Security; investments; retirement plans; and disability compensation from VA. Median income excludes VA disability compensation. That disability compensation is untaxed and is provided to veterans with medical injuries or conditions that were incurred or aggravated during active-duty military service.

CBO did not adjust the data to account for characteristics other than age and veteran status.

VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Certain dissimilarities between younger and older Vietnam veterans make it doubtful that younger veterans will ever have the same amount of income as older veterans. In effect, there were two sets of Vietnam veterans, rather than a single group. Older veterans probably earned more than younger veterans while working. They entered the military before the war escalated in 1965, were less likely to have been drafted, and were more likely to have had careers in the military and to collect military retirement pay after a 20-year career. As previously observed, a greater share of older veterans had college degrees than younger veterans. In addition, the share of older veterans with low test scores upon entry into the military was smaller than the share of younger veterans.28 They also probably differed in other ways that affected their income in retirement.

Income Distribution. To exclude extremely high and low values that might have skewed income findings, CBO also examined median income (the midpoint value in the income range) for veterans and nonveterans. Excluding disability payments, at age 71, median income for veterans ($44,200) was higher than for nonveterans ($41,800).29 (See Figure 5, bottom panel.)

Comparing veterans’ and nonveterans’ income distribution (excluding VA’s disability payments) confirmed that fewer veterans had low or high income (see Figure 6). When income for all men ages 63 to 78 was grouped into quintiles, only 15 percent of veterans fell into the bottom quintile, compared with 22 percent of nonveterans. Even in the bottom quintile, veterans’ income was 10 percent higher than nonveterans’ income. In addition, disability compensation and other benefits like free health care and special pensions for poor veterans (neither of which were included in CBO’s calculations) probably helped support the neediest veterans. On the opposite end of the income distribution, 17 percent of Vietnam veterans and 21 percent of nonveterans had income in the highest quintile; nonveterans in that quintile had average annual income that was more than 10 percent higher than veterans’ income.30

Figure 6.

Share of Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans Ages 63 to 78 in Each Income Group, 2018

Income was distributed more equally among veterans than among nonveterans.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Includes income from earnings (wages, salaries, and self-employment); Social Security; investments; and retirement plans. Excludes income from disability compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Bars for veterans add up to 100 percent, as do bars for nonveterans.

Common Components of Income

Although Vietnam veterans and nonveterans relied on many of the same sources of income, some sources were more important for veterans. On average, Vietnam veterans had a greater share of annual income from Social Security and retirement plans than nonveterans, who remained more reliant on earnings even in old age. That was also true when men at veterans’ modal age of 71 were examined (see Table 2). CBO looked at income by age because the sources and amounts of income differ by age.

Table 2.

Average Income for Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans at Age 71, by Source, 2018

2018 Dollars

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey and Department of Veterans Affairs.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Income refers to income from five sources: earnings (wages, salaries, and self-employment); Social Security; investments; retirement plans; and disability compensation from VA. Disability compensation is untaxed and is provided to veterans with medical injuries or conditions that were incurred or aggravated during active-duty military service.

VA= Department of Veterans Affairs; n.a. = not applicable.

Earnings. On average, working Vietnam veterans ages 63 to 78 earned $52,800 annually, 23 percent less than other working men ($68,700). For men at age 71, the difference was smaller: Veterans earned $50,500, and nonveterans earned $62,200 (see Figure 7, top panel). The earnings gap was larger for younger men than for older men.

Figure 7.

Earnings of Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans and Share Who Worked, 2018

Most men over age 65 no longer worked. Among those who did, Vietnam veterans earned less than nonveterans.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Shaded area denotes the largest three-year cluster of veterans who served in the Vietnam War (one-third of total). Veterans in that cluster probably served from 1966 to 1969, when forces were largest.

Earnings refer to wages, salaries, and self-employment income. Working individuals are those with nonzero earnings.

CBO did not adjust the data to account for characteristics other than age and veteran status.

The gap between veterans and nonveterans’ earnings for those who worked occurred partly because a large share of less-educated nonveterans—who probably had lower-wage jobs—had left the workforce by 2018. Their departure raised the average wage for nonveterans who kept working. In addition, just half of working veterans were employed full time, compared with 62 percent of working nonveterans.

Because most men between the ages of 63 and 78 were not working, the average earnings among all of them were much lower: $14,900 for veterans and $28,200 for nonveterans. For men age 71, the difference was smaller: those averages were $12,400 and $18,800, respectively. However, earnings were becoming a smaller share of total income for all men in retirement.

Part of the difference in average earnings arose because there was a gap in the share of veterans and nonveterans who were employed at age 63 or older (see Figure 7, bottom panel). The gap in employment was largest at age 63, indicating that veterans left the workforce at younger ages than nonveterans. Veterans may have stopped working earlier for several reasons, including their higher disability rates or the possibility that VA’s disability compensation enabled them to leave the labor market earlier.

Among men with self-employment income in 2018, nonveterans were a little more likely than Vietnam veterans to report such income, and on average they reported more: $47,800, compared with $36,600 for veterans. Self-employment was the main source of earnings for about 30 percent of all men with earnings income.31

Social Security. Participation in Social Security was extremely high for all men CBO studied. Almost all Vietnam veterans (94 percent) and nonveterans (90 percent) received payments at age 71 (see Figure 8, bottom panel).32 The share of veterans that collected Social Security benefits grew with each year of age until age 71 and then remained flat.

Figure 8.

Social Security Payments to Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans and Share Who Received Them, 2018

Vietnam veterans claimed Social Security earlier and received about the same amount as nonveterans.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Shaded area denotes the largest three-year cluster of veterans who served in the Vietnam War (one-third of total). Veterans in that cluster probably served from 1966 to 1969, when forces were largest.

Social Security payments include retirement, disability, and survivors’ benefits, as well as payments made by the U.S. Railroad Retirement Board.

CBO did not adjust the data to account for characteristics other than age and veteran status.

Veterans’ average annual Social Security payment was $17,900, much higher than nonveterans’ $13,900 average payment. That is generally explained by the fact that more veterans than nonveterans received Social Security benefits. A larger share of veterans (88 percent) than nonveterans (69 percent) had turned 66 by 2018, the age at which they were eligible for full Social Security benefits.33 In addition, many veterans claimed Social Security benefits earlier than nonveterans (in general, however, claiming benefits early decreases the monthly payment for that recipient).

When only men who received Social Security payments were considered, a small difference persisted, but only at certain ages and levels of income. Veterans who received payments collected, on average, $20,800; nonveterans collected $20,000, about $800 less.

At age 71, Social Security income was about the same for veterans and nonveterans (see Figure 8, top panel). Veterans younger than 71 collected slightly less in Social Security benefits, and veterans older than 71 collected more. Strikingly, even those older veterans with lower earnings in 2008 collected more Social Security benefits than nonveterans, on average.

CBO examined special earnings credits toward Social Security that Vietnam veterans received. But those credits probably do not explain older veterans’ bigger Social Security payments. (Those additional credits were not added to veterans’ Social Security payments; rather, they increased the total amount of income Social Security considered when setting monthly benefits.) Veterans on active duty from 1957 through 1977 were credited with $300 in additional earnings for each calendar quarter in which they received basic pay. For veterans who continued serving after 1977, the calculation for the credits changed but the maximum remained $1,200 per year. (In January 2002, the extra earnings credits ceased.)

CBO concluded that the formula used to calculate benefits was the most likely explanation for the difference between average Social Security payments for older veterans and nonveterans.34 Nonveterans were more likely to have had very low or very high earnings than veterans during their working lives, which might have generated a disparity in average Social Security benefits. Benefit amounts for very high earners—more of whom were nonveterans—replace a much smaller share of earnings than for others; benefits for low earners—more of whom were also nonveterans—more closely reflected their lower earnings. Thus, the group of nonveterans qualified for a slightly smaller amount of Social Security benefits, on average.

Investments. About 30 percent of veterans and nonveterans received investment income, and it was a small share of total income for all recipients except the wealthiest. The share of all men with investment income increased from less than 10 percent in the lowest income quintile to more than 50 percent for those in the highest quintile. Men in the lowest income group received an average of less than $500 annually; those with total annual income in the top quintile collected roughly $30,000.35

A slightly smaller share of Vietnam veterans younger than 71 reported investment income compared with nonveterans. Among men 71 and older, a bigger share of veterans had such income than nonveterans. Among all recipients, average income from investments was $19,900 for veterans and $26,800 for nonveterans. At age 71, veteran recipients reported $19,200 in investment income and nonveteran recipients $28,000, a difference of $8,800 (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Investment Income of Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans and Share Who Received It, 2018

Most men did not receive income from investments. Among those who did, Vietnam veterans received much less than nonveterans.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Shaded area denotes the largest three-year cluster of veterans who served in the Vietnam War (one-third of total). Veterans in that cluster probably served from 1966 to 1969, when forces were largest.

Investment income is from assets: interest, dividends, royalties, rents, and income from estates or trusts.

CBO did not adjust the data to account for characteristics other than age and veteran status.

Average investment income was smaller when the average includes people who did not receive such income. It was less, on average, for veterans than for nonveterans. For 71-year-olds, investment income averaged $6,400 for veterans and $9,200 for nonveterans. In general, amounts were greater for older men regardless of their veteran status. Investment income for older households—generally, those with at least one person age 65 or older—has been declining since the 1990s because fewer and fewer adults own financial instruments.

Retirement Plans. Employer-sponsored retirement plans were an important source of income for older Americans. On average, Vietnam veterans had about one-third more income from retirement plans in 2018 than nonveterans, ($20,300 and $15,300, respectively), probably in part because veterans were much more likely to have held jobs that offered such plans. At age 71, veterans had, on average, more income from retirement plans than nonveterans: $21,000 and $18,000, respectively (see Figure 10, top panel).

Figure 10.

Income From Retirement Plans for Vietnam Veterans and Nonveterans and Share Who Received It, 2018

Vietnam veterans were much more likely than nonveterans to receive income from retirement plans, but those who received payments took in less on average than nonveterans.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Shaded area denotes the largest three-year cluster of veterans who served in the Vietnam War (one-third of total). Veterans in that cluster probably served from 1966 to 1969, when forces were largest.

Retirement plans include defined-benefit and defined-contribution plans from companies, unions, and federal, state, and local governments (including the military); individual retirement accounts; Keogh plans; and any other type of pension, retirement account, or annuity.

CBO did not adjust the data to account for characteristics other than age and veteran status.

A much bigger share of veterans than nonveterans received payments from retirement plans. The gap was about 30 percentage points for the youngest men but shrank to about 17 percentage points by age 66 (see Figure 10, bottom panel). The finding suggests that, in addition to having greater access to retirement plans, Vietnam veterans began drawing income from their retirement plans earlier than other men.

As CBO’s 2008 analysis of earnings showed, more veterans than nonveterans were likely to have held jobs that included a defined benefit or defined contribution plan. For example, about 20 percent of Vietnam veterans had a government job, compared with 15 percent of nonveterans.36

Federal workers have access to both defined benefit and defined contribution plans. State and local government workers commonly have access to only a defined benefit plan, and private-sector workers typically have access only to a defined contribution plan. Access to and participation in any type of retirement benefit is much greater for government workers; in 2008, about 85 percent of government employees participated in a retirement plan compared with about 50 percent of private industry workers. In addition, more nonveterans than veterans were self-employed and were less likely to have defined benefit retirement plans.

The military offers separate retirement plans (including a defined benefit plan that is usually available after 20 years of service). In 2018, a little over 10 percent of Vietnam veterans collected a military pension, CBO estimates. Although relatively few Vietnam veterans qualified for retirement benefits from the military, those who did would typically have been in their late 30s or early 40s when they separated from service; they could have joined the civilian labor force and had second careers, adding to their retirement income.

When income from retirement plans is averaged only among those who received it rather than among all men, average annual payments were a bit smaller for Vietnam veterans ($26,800) than for nonveterans ($28,200). At the modal age of 71, veterans collecting retirement income also received less ($27,500) than nonveterans ($29,500). Vietnam veterans older than 73, though, received about $1,500 more, on average, than nonveterans. The payment differences can probably be explained by the nature of the jobs each group held while working.

Disability Compensation From the Department of Veterans Affairs

In addition to the four sources of retirement income that could be collected by all men, some veterans also collected disability payments from VA for injuries or medical conditions they received or developed during active-duty service. (See Box 1 for detail on VA’s disability program and other benefits for veterans.) The average payment for recipients in 2018 was $18,100, so VA’s disability payments were a substantial part of income for some veterans. About 24 percent of Vietnam veterans received disability payments, CBO estimates.

Box 1.

Benefits Provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides benefits for Vietnam veterans because of their military service. Three of those benefits can be substantial: disability compensation, medical care, and pensions. Other benefits that VA provides tend to be smaller or are not available to Vietnam veterans.1

Disability Compensation

VA’s disability compensation program is the department’s largest program. In 2018, it provided payments to nearly one-quarter of all veterans. Of those receiving compensation, 1.3 million were from the Vietnam era, ages 63 to 78; VA spent roughly $25 billion on them in that year.

The disability compensation provided by the agency is a tax-free payment to veterans who have medical conditions or injuries that were incurred or aggravated during active-duty military service (service-connected disabilities). VA compensates veterans for a wide variety of conditions, from tinnitus (ringing in the ears) to post-traumatic stress disorder to lost limbs. The amount of the payment is linked to a composite disability rating that VA assigns to each disabled veteran. That rating ranges from zero to 100 percent in increments of 10.2 In calendar year 2018, base (minimum) payments ranged from about $135 per month to about $2,975 per month depending on disability rating; some veterans also received supplemental payments.

Unlike federal and private-sector disability insurance, which generally goes to people whose disease or injury affects their ability to work, VA’s ratings and base disability payments do not take account of veterans’ employment status, earnings, ability to work, or age. Veterans can receive disability payments no matter how much other income they have.3

Medical Care

VA’s medical services are broad in scope and include hospital care, outpatient primary and specialty care, counseling services, rehabilitation and prosthetic care, and prescriptions. VA operates a network of 170 medical centers and more than 1,000 outpatient clinics, rehabilitation facilities, and nursing homes. Veterans may receive medical care at those facilities or, in some circumstances, VA may pay for private care in their communities. Most services and products are delivered in VA’s facilities at little or no cost to veterans.

In 2018, about 9 million veterans were enrolled in VA’s medical care program. CBO estimates that nearly 3 million of them had served during the Vietnam War. Most Vietnam veterans are eligible for VA medical care but, like other veterans, they must enroll to receive treatment.4 In 2018, roughly one-half of Vietnam veterans enrolled in VA health care were ages 67 to 71.

In 2018, nearly 55 percent of those ages 65 to 74 who were enrolled in VA’s medical care (most of whom were Vietnam veterans) had service-connected disabilities, and another 18 percent had low income and no service-connected disabilities. (VA set the threshold for low income at about $34,000 for veterans without dependents.) Veterans those ages were more likely to use VA’s medical care than were other enrolled veterans; in 2018, about 75 percent did so, compared with about two-thirds of all enrollees. (Not all enrollees seek care in any given year.)

Enrollees in the 65- to 74-year-old age group were among the most expensive to care for, costing about $11,400 in 2018, on average. Not only did members of that age group have a high rate of service-connected disabilities, but their health conditions probably worsened or new conditions developed as they aged. Nor did VA’s care reflect all of the expenses the government incurred in treating them: Because most veterans begin using Medicare when they reach 65, Medicare picks up a large share of their costs, and VA’s cost per enrollee drops at that age. Vietnam veterans who enrolled in VA’s medical care were more likely to be in the lower half of the income distribution.

Pensions

Unlike a private-sector pension program, VA pensions are means-tested, aiming to provide support to older veterans with little or no income and few assets. Veterans whose income is low and who served during wartime may be eligible for VA’s pensions if they meet certain other criteria.5 The maximum annual pension in 2018 was $13,166 for a veteran with no dependents. The pension amount is reduced by the amount of a veteran’s other income.6

Only 260,000 veterans collected a pension from VA in 2018. More than half, 160,000, were Vietnam veterans. The average pension amount for Vietnam-era recipients in 2018 was about $12,350. Because so few veterans receive pension payments, however, when averaged among all Vietnam veterans, the average annual benefit is small. CBO did not include that pension income in its analysis, mainly because ACS data combine VA’s pension payments with several other types of income.

1. Among its programs, the department also offers education and vocational rehabilitation assistance; provides benefits for widowed spouses and children; offers life insurance; guarantees home loans to veterans; and manages veterans’ cemeteries. Basic eligibility for VA’s benefits varies by program. Most programs set minimum active-duty requirements (such as length of active duty service and the nature of service). For example, to be eligible for VA medical care, Vietnam veterans generally must have received a military discharge other than dishonorable. VA may also consider other factors, such as current income and time since discharge from the military, in providing specific benefits.

2. The rating for any individual condition is linked to clinical severity; higher composite ratings generally reflect more disabilities or more severe disabilities, and veterans with higher ratings are compensated at higher rates.

3. For more detail on VA’s disability program, see Congressional Budget Office, Veterans’ Disability Compensation: Trends and Policy Options (August 2014), www.cbo.gov/publication/45615.

4. Veterans are assigned to one of eight priority groups based on their service-connected disabilities, income, combat status, and other factors. The highest-priority groups, groups 1 to 3, primarily include veterans who have service-connected disabilities. Priority group 4 includes veterans who are housebound or are catastrophically disabled. Priority group 5 contains lower-income veterans. Priority group 6 includes special populations of veterans, including veterans who served in Vietnam and do not qualify for a higher priority group. The lowest-priority groups, 7 and 8, include higher-income veterans without compensable service-connected disabilities. New enrollment in priority group 8 has been restricted since 2003. For a fuller description, see Department of Veterans Affairs, “VA Health Care Enrollment and Eligibility” (April 23, 2019), https://go.usa.gov/xGSAb.

5. A small number of veterans receive pensions under different eligibility and payment rules.

6. Additional amounts may be paid to veterans who have dependents, who are in need of the aid and attendance of another person, or who are housebound, as determined by VA.

For Vietnam veterans ages 63 to 78, including those who did not receive disability payments, the average annual disability payment was $4,300; the average payment at age 71 was $4,900 (see Figure 11). Those payments make up much of the average difference in other income between veterans and nonveterans, increasing veterans’ average income by about 7 percent to $63,300.

Figure 11.

VA Disability Payments to Vietnam Veterans and Share Who Received Them, 2018

Most Vietnam veterans did not receive disability compensation from VA. Those who did received an average of $18,100.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the American Community Survey.

The Vietnam War ran from August 1964 (fiscal year 1965) to January 1973.

Shaded area denotes the largest three-year cluster of veterans who served in the Vietnam War (one-third of total). Veterans in that cluster probably served from 1966 to 1969, when forces were largest.

The Department of Veterans Affairs provides tax-free disability compensation to veterans with medical injuries or conditions that were incurred or aggravated during active-duty military service.

CBO did not adjust the data to account for characteristics other than age.

Vietnam veterans who received disability payments from VA were likely to be in the lower half of the income distribution for all men in the age range that CBO analyzed. In addition, they had less income from other sources than veterans who did not receive VA payments, mainly because they were less likely to be employed and because those who were employed had lower earnings. However, on average, their disability payments made up that difference, increasing the average total income of veterans who received those payments above the average income of veterans who did not.

The incidence and amount of disability payments from VA varied by age. A greater share of Vietnam veterans who were 68 to 71 years old in 2018 received disability payments (28 percent) than veterans of other ages (22 percent). Furthermore, partly because those 68- to 71-year-olds were also likely to have higher disability ratings (70 percent or more), CBO estimates that the average payments for that age group were about $19,400 a year, $1,300 more than the $18,100 average payment for all Vietnam veterans receiving VA disability compensation.

Because Vietnam veterans ages 68 to 71 were likely to have served in the mid- to late 1960s, when deployments to Vietnam and surrounding countries were largest, they may have been more likely to experience combat-related injuries and medical conditions, some of which did not show up immediately. Although veterans claim far more disabilities than the number of combat injuries reported at the time (about 150,000), many medical conditions can take years to develop (such as limitations on joint movement) or may not be identified at the time (such as mental illnesses).

In addition to such late-onset or previously unrecognized conditions, VA has declared that several medical conditions can be presumed to have been caused by the service member’s deployment to Vietnam. Those presumptive conditions substantially increase the number of veterans who receive disability payments.37 Among such presumptive conditions are diabetes, certain cancers, and other problems that may have arisen from exposure to Agent Orange or other herbicides during the war. A sizable share of Vietnam veterans receive VA disability payments for presumptive conditions. For instance, VA administrative data showed that nearly 375,000 Vietnam veterans received disability compensation for diabetes in 2018; nearly all of those cases were considered presumptive conditions.

Limitations of CBO’s Study

CBO’s study has limitations that are common to any analysis based on survey data. Survey data may be inaccurate because of misreporting. Some people may not answer certain questions or underreport the amount they receive from particular sources. Both problems have been extensively noted.38

The Census Bureau uses a statistical approach to estimate the values of missing responses. CBO also used statistical methods to assign Social Security and retirement-plan income to some respondents. About 95 percent of men ages 60 or older in the ACS correctly responded that they received Social Security benefits, according to administrative data. However, nearly 20 percent underreported the amount of Social Security benefits they received. CBO therefore imputed additional Social Security income to those who reported that they had received it. Some of those who receive income from retirement plans do not report it at all, so CBO imputed such income to some respondents. For a discussion of CBO’s approach to imputing retirement-plan income, see the appendix.

CBO did not adjust ACS’s data for earnings or investment income. Information about wages and salaries is generally reported correctly. The exception is self-employment income, which is subject to nonresponse and underreporting.39 Likewise, investment income is subject to nonresponse and underreporting. For those income sources, there is no consensus on how to account for those problems. However, the consequences of nonresponse and underreporting in those two categories probably had a minimal effect on this report: In the United States, self-employment and investments are a small portion of total annual income for most retired men.40

CBO also used VA’s data to estimate the amount of disability compensation Vietnam veterans received. That was necessary because ACS data only included the number of people receiving VA disability compensation, not the amount of that compensation. CBO adjusted ACS’s profile for those veterans on the basis of VA’s aggregate data. It then used VA’s data on total spending and average payments by disability rating to estimate the average amount of payments to Vietnam veterans by age.

1. In this report, the term Vietnam veteran refers to any male veteran who served on active duty in the military during the Vietnam War, regardless of the type or location of service. The available data do not distinguish between the 40 percent of veterans who were deployed to combat zones and those who served in the United States or in other locations overseas. When referring to nonveterans, this report means any man who was between the ages of 63 and 78 in 2018 and who did not serve on active duty in the U.S. armed forces.

2. Two studies focused on the causal effects of military service on the earnings of Vietnam veterans born between 1950 and 1953 who had been subject to a draft lottery. See Joshua D. Angrist, Stacey H. Chen, and Jae Song, “Long-Term Consequences of Vietnam-Era Conscription: New Estimates Using Social Security Data,” American Economic Review, vol. 101, no. 3 (May 2011), pp. 334–338, https://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.334; and Joshua D. Angrist, “Lifetime Earnings and the Vietnam Era Draft Lottery: Evidence from Social Security Administrative Records,” American Economic Review, vol. 80, no. 3 (June 1990), pp. 313–336, www.jstor.org/stable/2006669.

3. Because there was no official declaration of war, government entities, national surveys, and researchers define the start and end dates of the Vietnam War differently. CBO uses August 1964 and January 1973 as the start and end points for the war. Those dates are also used by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, and the Selective Service, although not consistently. For example, the qualification dates for some types of benefits are different.

4. Fewer than 300,000 women served in the Vietnam era. Women’s participation was capped at 2 percent of enlisted personnel until 1967, when a new law removed the cap (Public Law 90-130; 81 Stat. 374).

5. See Richard Cooper, Military Manpower and the All-Volunteer Force, R-1450-ARPA (RAND Corporation, 1977), www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R1450.html.

6. See David Chu and Eva Norrblom, Physical Standards in an All-Volunteer Force, R-1347-ARPA/DDPAE (RAND Corporation, 1974), www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R1347.

7. In 1965, President Johnson made a significant change to the system when he repealed the exemption for married men (Executive Order 11241).

8. It was also possible to avoid military service by evading the draft. Some men avoided military service by deliberately failing the physical exam or by joining the National Guard and reserves, from which few men were activated. One source calculated that more than 15 million men were deferred, exempted, or disqualified, and about 600,000 were apparently draft offenders. See Lawrence M. Baskir and William A. Strauss, Chance and Circumstance: The Draft, the War and the Vietnam Generation (Alfred A. Knopf, 1978); and George Flynn, The Draft: 1940–1973 (University Press of Kansas, 1993).

9. Military pay refers to regular military compensation, which includes basic pay, tax-exempt allowances for housing and food, and an estimate of the tax benefit associated with those allowances.

10. For more information on the mortality rates of Vietnam veterans, other veterans, and nonveterans, see Joshua D. Angrist, Stacey H. Chen, and Brigham R. Frandsen, “Did Vietnam Veterans Get Sicker in the 1990s? The Complicated Effects of Military Service on Self-Reported Health,” Journal of Public Economics, vol. 94, no. 11–12 (December 2010), pp. 824–837, https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubec0.2010.06.001; Janet Wilmoth, Andrew S. London, and Wendy M. Parker, “Military Service and Men’s Health Trajectories in Later Life,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, vol. 65B, no. 6 (2010), pp. 744–755, https://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbq072; and Tegan K. Catlin Boehmer and others, “Postservice Mortality in Vietnam Veterans: 30-Year Follow-up,” Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 164, no. 17 (2004),pp. 1908–1916, https://tinyurl.com/y6d8pvhc.

11. See Karl E. Cocke, Department of the Army Historical Summary: Fiscal Year 1974, (Center of Military History, 1978), pp. 120–121, https://go.usa.gov/xGSA6. In addition, in its 1979 Annual Report, VA stated that more than 800,000 active duty personnel and veterans who had neither completed high school nor received an equivalency certificate enrolled in courses or other special assistance programs “to overcome those education disadvantages.” See Administrator of Veterans Affairs, 1979 Annual Report, www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/FY1979.pdf (21.7 MB).

12. Among other benefits, under the first GI Bill, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the government fully covered tuition and living expenses for most four-year undergraduate programs in the mid- to late 1940s. Similarly comprehensive GI Bills were enacted for the Korean and Vietnam wars.

13. David Card and Thomas Lemieux have estimated that draft avoidance raised college attendance rates by 4 to 6 percentage points in the late 1960s and increased the share of men with a college degree. But those increases were offset by an overall decline in college attendance among those born in the 1950s. Factors such as changes in the perceived returns to education presumably depressed college enrollment. See David Card and Thomas Lemieux, “Going to College to Avoid the Draft: The Unintended Legacy of the Vietnam War,” American Economic Review, vol. 91, no. 2 (May 2001), pp. 97-102, https://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.2.97. School attendance by service members was also high: The Army reported that participation in its educational programs for active personnel, including college completions, had never been as high as it was in fiscal year 1974.

14. The share of Black men in the enlisted ranks was substantially higher in the early years of the all-volunteer force. See Richard N. Cooper, Military Manpower and the All-Volunteer Force, R-1450-APPA (RAND Corporation, 1977), p. 210, www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R1450.html.

15. For this analysis, a respondent was considered functionally disabled if he answered yes on the American Community Survey (ACS) to at least one of six questions regarding serious difficulty with hearing, seeing, remembering, moving (such as walking or climbing stairs), self-care, or independent living.

16. Studies have found higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among Vietnam veterans, though estimates differ. One study estimated that 15 percent of all male Vietnam veterans had combat-related PTSD in 1988; another study found a 9 percent rate of PTSD in 1988. (About 4 percent of all men develop PTSD at some point in their lives.) See Richard A. Kulka and others, The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study: Tables of Findings and Technical Appendices (prepared by Research Triangle Institute for the Veterans Administration, November 1988), https://go.usa.gov/xGSf8 (PDF, 22.9 MB); Bruce P. Dohrenwend and others, “The Psychological Risks of Vietnam for U.S. Veterans: A Revisit With New Data and Methodologies,” Science, vol. 313, no. 5789 (August 18, 2006), pp. 979–982, https://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1128944; and Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for PTSD, “How Common Is PTSD in Adults?” (accessed October 14, 2020), www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp.

17. See Joshua D. Angrist, Stacey H. Chen, and Brigham R. Frandsen, “Did Vietnam Veterans Get Sicker in the 1990s? The Complicated Effects of Military Service on Self-Reported Health,” Journal of Public Economics, no. 94, issue 11–12 (December 2010), pp. 829–839, https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubec0.2010.06.001; and Lynn H. Gerber and others, “Disability Among Veterans: Analysis of the National Survey of Veterans (1997-2001),” Military Medicine, vol. 181, no. 3 (March 2016), pp. 219–226, https://dx.doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00694.

18. It is unclear whether veterans with a service-connected disability rating are more or less likely to report functional disabilities than nonveterans or than veterans without disability ratings.

19. See Richard Johnson and Nadia Karamcheva, “What Determines Gradual Retirement? Differences in the Path to Retirement between Low- and High-Educated Older Workers” (paper presented at the Allied Social Science Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, January 6-8, 2017).

20. The most recent data available at the time of analysis were for 2018. For the ACS data and its documentation, see Census Bureau, U.S. Census Data for Social, Economic, and Health Research, “IPUMS-USA: Version 10.0” (accessed September 1, 2020), https://dx.doi.org/10.18128/D010.V10.0.

21. The ACS asks whether the respondent ever served on active duty in the armed forces, reserves, or National Guard. For those who answer yes, a follow-up question asks when the respondent served on active duty. ACS defined those on active duty between August 1964 and April 1975 as Vietnam veterans. The vast majority of respondents in the sample who reported military service during that period would have been in the active component because only about 25,000 reservists were mobilized in the Vietnam War.