Note

This document is one in a series of primers explaining various elements of CBO’s work to support the budget process and to help the Congress make budget and economic policy. It updates and supersedes How CBO Prepares Baseline Budget Projections, published in February 2018. This and other primers in the series are available on the agency’s website at www.cbo.gov/topics/budget/budget-concepts-and-process.

The Congressional Budget Act of 1974, often called the Budget Act, established the House and Senate Committees on the Budget to set broad federal tax and spending policy and identify priorities for allocating budgetary resources. To help those committees carry out their responsibilities, the Budget Act also established the Congressional Budget Office and required it to produce an annual report on federal spending, revenues, and deficits or surpluses, as well as subsequent revisions to that report as may be necessary.

To fulfill that requirement, CBO provides the Congress with projections of revenues from each major revenue source, spending for every federal budget account, and the resulting deficits or surpluses, along with forecasts of the nation’s economy for the current fiscal year and for the ensuing 10 years. Those projections, which constitute CBO’s budget baseline, are developed under the assumption that current laws governing taxes and spending generally remain in place.

Baseline projections supply the Congress with information about the budgetary outlook over the coming decade under current laws and a benchmark to use in determining whether proposed legislation is subject to various budget enforcement procedures. Most of the rules that govern the baseline are specified in law, although some have been developed jointly by the House and Senate Committees on the Budget, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and CBO. This document provides answers to questions that CBO is frequently asked about how it prepares its baseline projections.

CBO’s baseline projections, along with information about its economic forecast, are available on the agency’s website. For an explanation of key terms used throughout this report, see Common Budgetary Terms Explained; for detailed definitions, see CBO’s Glossary.

What Is the Baseline?

CBO’s baseline is a set of detailed projections of federal spending, revenues, deficits or surpluses, and debt for the current year and the decade that follows. Those projections inform policymakers about budgetary trends and the nation’s fiscal condition under current law; they are not meant to predict future outcomes, because they cannot account for future legislation.

CBO’s projections are published as tables and described narratively in its publications, primarily in a set of regular reports called The Budget and Economic Outlook and in supplemental data provided with those reports. In keeping with its mandate to provide objective, impartial analyses, CBO never makes recommendations about policies or legislation.

Because revenues from various sources and spending on many programs depend on economic factors such as economic growth and inflation, CBO’s baseline budget projections rely on the agency’s economic forecast. Like the budget projections, that forecast reflects the economic effects of fiscal policy in accordance with current law and is developed to represent roughly the middle of the range of likely outcomes for the U.S. economy.1

CBO’s baseline projections are the result of a process that at various stages involves most of the agency’s staff. In general, the process of developing a projection for a spending account or revenue source consists of:

- Analyzing recent patterns in spending and revenues,

- Incorporating CBO’s economic forecast,

- Incorporating the effects of recent legislation and administrative actions,

- Modeling various components of the account appropriately, and

- Reviewing the resulting projections.

How Is the Baseline Used by CBO and the Congress?

In addition to providing the basis for The Budget and Economic Outlook, CBO’s analyses of the President’s annual budget request, and other reports, CBO’s baseline is the foundation for the agency’s cost estimates for proposed changes in law that would affect mandatory spending or revenues.2 Unlike estimates for legislation affecting mandatory programs or revenues, estimates of the costs of discretionary appropriations are generally not affected by baseline projections, because those projections require assumptions about future appropriations. Rather, discretionary costs are estimated in relation to current law (that is, appropriations are assumed not to continue) rather than in relation to the baseline.

The Budget Committees generally use CBO’s baseline projections, most often those released in the spring around the same time as CBO’s analysis of the President’s budget request, to underlie the Congressional budget resolution. The effects of most legislation on mandatory spending and revenues are estimated in relation to the baseline that underlies the budget resolution.

CBO’s baseline also underlies its long-term budget projections (which span 30 years) and is brought to bear in the agency’s analytical research and reporting to assess the effects of proposed changes in fiscal policy.3

When Does CBO Produce Its Baseline, How Long Does It Take, and What Resources Are Required?

CBO typically releases its initial annual baseline—the agency’s most comprehensive undertaking—in January or February. Updates to the baseline usually follow once or twice each year to incorporate information from the President’s budget and other information that becomes available.

The process of producing most projections of spending and revenues for each year’s initial baseline takes roughly two months. (Before that work begins, CBO develops an economic forecast to serve as the basis for baseline projections, and staff members analyze actual results for the recently completed fiscal year.) About half of that time is needed to update and revise all spending and revenue projections. The other half is needed for analysis of the information, writing, and production of accompanying reports. For some of CBO’s work, the process of producing baseline projections starts even earlier in the year.

The projection process involves most of CBO’s staff—analysts, managers, and support staff from every division in the agency. Some staff spend most of their time on work related to the baseline; others provide analytical support for the projection models, review the projections, and prepare The Budget and Economic Outlook and supporting materials for publication. The staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) also provides information about recently enacted tax legislation and estimates of the budgetary effects of extending expiring tax provisions.

What General Principles Guide the Work?

CBO’s goal is to develop projections that are as accurate as possible, under the assumption that current laws governing taxes and spending generally remain in place. To achieve that goal, analysts assess the factors that affect each federal program or revenue source using data and other information from a broad range of sources.

In line with its goal for accuracy, CBO aims to develop projections that reflect the middle of the range of likely outcomes in most cases.4 Therefore, CBO’s analysts often test the sensitivity of their projections to identify the range of possible outcomes. Additionally, an analyst may assess whether a projection is roughly as likely to be too high as too low. For major spending accounts and revenue sources, analysts routinely test how sensitive baseline projections are to specific factors by observing the way that projections change as particular factors come into play.

What Information Does CBO Rely on to Produce Baseline Projections?

CBO relies on information from sources throughout the federal government, including OMB, the Department of the Treasury (including the Internal Revenue Service), executive branch agencies’ budget and program offices, the government’s statistical agencies, JCT, the Government Accountability Office, and the Congressional Research Service. Additionally, CBO’s analysts confer with experts outside the federal government—from think tanks, universities, interest groups, state and local governments, and elsewhere—who represent a breadth of perspectives and disciplines. CBO also extensively analyzes data acquired from private organizations.

CBO’s Panel of Economic Advisers, consisting of widely recognized experts, provides assistance with a broad range of topics. Members of the agency’s Panel of Health Advisers are experts in health policy and the health care sector. CBO hosts meetings of the advisers and routinely solicits their views between meetings. Through those interactions, CBO benefits from the advisers’ understanding of current research and their reviews of the agency’s economic forecast and health analysis.

How Does CBO Ensure That Its Baseline Projections Are as Accurate as Possible?

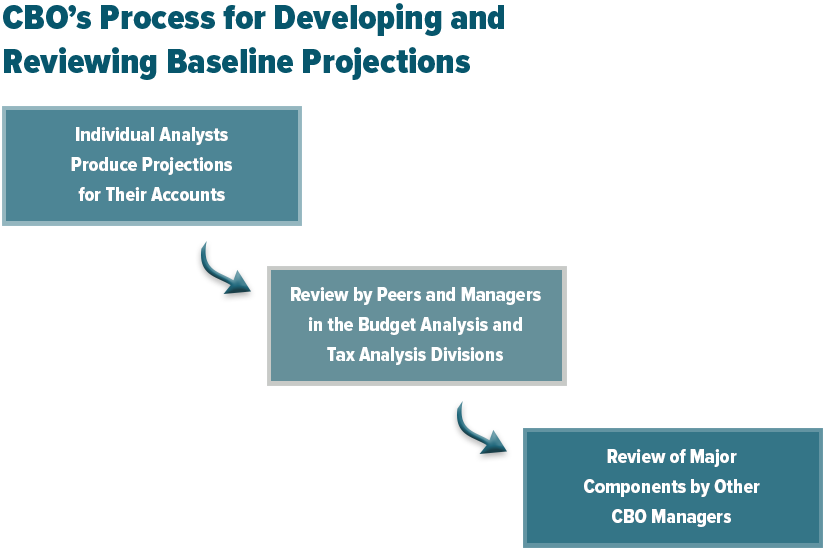

CBO rigorously reviews its estimates before they are published. Individual analysts, peer reviewers within the agency, and CBO’s managers at all levels review projections for each spending account and revenue source to ensure that they are as accurate as possible (see Figure 1). The reviews focus on significant changes from previous projections and on current or potential issues that might arise with respect to enforcement of budget procedures.

The review process includes an examination of:

- Historical trends,

- The accuracy of previous projections,

- The relationship of budget authority to outlays over time,

- The relationship between revenues and associated macroeconomic income measures,

- Estimates (when they exist) from other organizations or experts, and

- Explanations of atypical patterns.

At formal review meetings, analysts and managers review the reasoning that underlies projections. In those discussions, they also examine changes in projections and identify their drivers (for example, the performance of the economy, technical aspects of program implementation, unanticipated events, or changes in law or policy). Once the review of all federal budget accounts is complete, the spending and revenue baselines are reviewed and checked for reasonableness and analytical soundness.

CBO seeks to improve the accuracy of its work by regularly assessing the quality of its past projections and identifying the factors that might have led to under- or overestimates of particular categories of federal revenues and outlays. Every baseline update offers the agency the opportunity to improve its projections and to refine its assessment of possible outcomes.

What Components of the Federal Budget Does the Baseline Include?

CBO’s baseline projections involve the four major components of the federal budget:

- Mandatory (or direct) spending, which is governed by statutory criteria and usually not constrained by the annual appropriation process;

- Discretionary spending, which is controlled by appropriation acts;

- Net spending for interest, the interest the government pays (which largely depends on the amount of debt held by the public and the interest rates on that debt) minus the interest it receives; and

- Revenues, including taxes, fees, and fines collected by the Treasury or other agencies.

Mandatory Spending

Mandatory spending consists of outlays for some federal benefit programs and certain other payments to people, businesses, nonprofit institutions, and state and local governments. It includes outlays for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, student loans, certain refundable tax credits, and other programs that generally are governed by statute rather than by specific annual appropriations. (Some mandatory programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, receive annual funding in appropriation acts.) The share of all federal outlays classified as mandatory spending has grown significantly over time and now comprises the majority of federal outlays.

Discretionary Spending

Funding for most discretionary programs is provided through annual appropriation acts and continuing resolutions in the form of budget authority—the authority provided by federal law to incur financial obligations that will result in immediate or future outlays of federal funds. (The Congress occasionally provides discretionary budget authority for multiple years at a time rather than annually.) Discretionary spending comprises spending for defense and nondefense activities. Defense discretionary spending consists of funding for various activities related to national defense, including military personnel, operations, maintenance, procurement, research and development, facilities, and defense-related nuclear programs. Nondefense discretionary spending comprises funding for education and training, transportation, certain veterans’ benefits, law enforcement, national parks, disaster relief, and foreign aid, among other activities.

Depending on the activity or program, federal outlays that arise from budget authority can occur over short periods (to pay salaries, for example) or longer ones (to pay for long-term research or construction). Therefore, discretionary outlays recorded each year come from budget authority provided by appropriation acts enacted for prior years in addition to those enacted for the current year.

Net Outlays for Interest

Net outlays for interest reflect the government’s interest payments on debt held by the public, such as Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, offset by interest income that the government receives and by other earnings.

Revenues

Federal revenues come from taxes imposed on individual and corporate income, employers’ payrolls, the production and importation of specific goods, and transfers of estates and gifts. Other receipts include remittances from the Federal Reserve System to the Treasury, fees imposed on various activities, and fines.

Individual income taxes constitute the largest source of federal revenues. Payroll taxes—mainly for Social Security and Medicare Part A (the Hospital Insurance program)—are the second-largest source, followed by corporate income taxes.

What Rules Govern the Baseline?

Most of the principles and rules that govern how the baseline is formulated are set in law. Others originated in budget resolutions, rules of the House or the Senate, conference reports that accompanied budget legislation, and the 1967 Report of the President’s Commission on Budget Concepts. Some rules have been developed jointly by the House and Senate Committees on the Budget, OMB, and CBO; such consultation is essential for resolving uncertainty about how to implement the rules in particular cases. (Although the Budget Act requires CBO to report projections to the Budget Committees each year, in most cases it does not specify the methods the agency should use to arrive at those amounts.)5

Particularly important is section 257 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (sometimes called the Deficit Control Act), amended several times since enacted, which defines the baseline and spells out some of the rules for projecting spending and revenues. Although CBO’s baseline generally reflects current law, including scheduled expiration dates for most tax provisions and some spending programs, the Deficit Control Act directs the agency to follow some rules that may lead to a different result for certain programs. In particular, the act directs the agency to:

- Assume full funding for benefits under entitlement programs even if the source of that funding is inadequate;

- Assume that many mandatory programs (and thus their spending) continue to operate throughout the baseline projection period after their scheduled expiration dates;

- Assume that excise taxes dedicated to trust funds are extended for the remainder of a projection period at their expiring rate; and

- Assume that appropriations grow each year with inflation, starting from the most recent discretionary appropriation, even if the appropriation is for an emergency or is widely viewed as a onetime appropriation.

Because CBO’s cost estimates for legislation affecting mandatory programs are developed in relation to the baseline, the Congress’s reauthorizing an expiring mandatory program often will not be shown as having a cost—even though it would have consequences for a program’s operation—because the program’s continuation is already assumed in the baseline.

What Is the Basic Approach to Developing the Baseline?

CBO’s baseline for spending is built from the bottom up. Projections are developed for each of the nearly 4,000 subaccounts in the federal budget (a subaccount is the most detailed level of spending for each account).

The revenue baseline is constructed from projections of tax, fine, and fee collections. Those projections are developed in various ways. For example, individual income taxes are projected using a microsimulation model reflecting information about individuals and households, including a sample of tax returns prepared by the Internal Revenue Service. In other cases, revenues are projected by applying the appropriate tax rate to the projected tax base to reflect current law. For example, CBO projects the amount of imports and then projects revenues from customs duties on the basis of the applicable customs duty rates. CBO also projects activities of the Federal Reserve and the resulting remittances to the Treasury.

For each spending account and source of revenues that CBO projects, analysts first compare the most recent actual results with earlier projections. They also examine legislation enacted in the interim as well as administrative or other changes that would affect spending, and they adjust projections accordingly. In addition, analysts incorporate the results of CBO’s economic forecast—accounting for the various ways that economic factors affect each spending account and source of revenues. Finally, CBO’s analysts assess any available program data, consider recent events and real-world effects, and otherwise apply expertise and knowledge about each federal program to estimate the costs of that program over the baseline period.

Analyzing Recent Spending and Revenues

The development of CBO’s initial annual baseline begins with an analysis of prior-year spending and revenue collections for each account and source of revenues. Analysts compare previous estimates of outlays and revenues in the baseline projections with the actual outlays recorded by the Department of the Treasury in its Daily Treasury Statement (DTS) and Monthly Treasury Statement (MTS), as well as with details from the department’s “Combined Statement of Receipts, Outlays, and Balances” and other reports from the Administration. That scrutiny allows analysts to determine the accuracy of their estimates and to identify sources of error.

If detailed information about spending and revenues is not available when CBO begins its analysis, analysts incorporate their own estimates of the disaggregated actual data into the agency’s updated projections. For example, some programmatic data lag behind overall outlay data by several months, and aggregated data about revenues are generally available a year or two sooner than are the detailed tax return data that form the basis of CBO’s various models. Because of such timing lags, analysts may incorporate into their models estimates of disaggregated recent spending and revenue collections, even though such estimates may end up being significantly different from the actual underlying details eventually reported.

When CBO assesses the factors that might explain actual amounts’ deviating from its estimates and from previous trends, it uses historical patterns and experience to inform those assessments and reflects the results in its projections. CBO may use its assessment—often in consultation with outside experts—to modify its modeling of the behavior of people and businesses. Other, unexpected results also may become evident, leading either to modifications of projections within the structure of CBO’s models or to other adjustments.

The agency generally expects—on the basis of historical experience—that effects from as-yet-unknown factors that cause revenues to deviate from model-based estimates will dissipate gradually over the course of a projection period. In the case of projections of revenues from individual income taxes, CBO’s analyses suggest that integrating that expectation into the agency’s projections tends to minimize forecast errors.6

When CBO updates its projections for baselines published later in the year, analysts take into account spending, obligations, and receipts for the current fiscal year by reviewing the most recent DTS, MTS, and other reports from the Administration. Analysts also study spending and revenue trends not only at the account or source level but also from a broader perspective of overall outlays and receipts.

Accounting for Changes in Policy

Estimates of spending and revenues generally reflect current law as it relates to the underlying programs or revenues, with the exception of certain rules governing the baseline that are outlined in the Deficit Control Act (see “What Rules Govern the Baseline?”). With each baseline update, CBO accounts for legislation enacted since the previous baseline was completed and for newly finalized regulations and administrative actions that are substantively different than previously expected. When an agency publishes a proposed regulation in the Federal Register, CBO generally does not incorporate into its baseline the full effect of the rule as proposed. Rather, CBO incorporates a probability (often 50 percent) that the rule will be implemented to reflect the uncertainty of whether and how the rule ultimately will be carried out.

Incorporating CBO’s Economic Forecast

CBO’s annual economic forecasts underlie, and are crucial for developing, the agency’s baseline budget projections. Forecasts of the nation’s economic output and interest rates are especially important, and various components of the baseline depend on other economic factors. For example, inflation is a significant factor for estimating the benefits paid through Social Security, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and other programs that may increase each year as a result of cost-of-living or other adjustments tied to inflation. In addition, as specified in the Deficit Control Act, CBO projects discretionary spending for individual programs by adjusting the amount of a current-law appropriation to account for inflation.

Projections of revenue collections are particularly sensitive to CBO’s economic forecast. As personal income, payrolls, corporate profits, imports, consumption of goods, and wealth increase, so do receipts from income and payroll taxes, customs duties, excise taxes, and estate and gift taxes. Because income and payroll taxes account for about 90 percent of federal revenues, CBO’s projections of revenues depend most heavily on its projections of wages, other personal income, and corporate profits. Most of those macroeconomic measures are projected using definitions from the national income and product accounts (or NIPAs, which are produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis in the Department of Commerce), but the tax bases correspond to measures defined by tax law. CBO accounts for differences between those measures when it projects revenues.

Ideally, the historical relationships between relevant economic indicators and tax revenues could be used in developing revenue projections. However, those relationships can be influenced by prior changes in law, so history is not necessarily a useful guide for projecting revenues under current law. To extrapolate into the future the historical relationship between revenues and gross domestic product or other macroeconomic indicators, CBO would need to quantify the effects of past changes in fiscal policy. If such effects were not appropriately accounted for, then the projections would implicitly reflect the assumption that in the future, changes in law would be similar to changes in the past that were enacted under similar economic conditions. Because of the difficulty in accounting for such effects, CBO does not use such a technique to project revenues.

Instead, CBO identifies the relationship between macroeconomic measures of the economy and the activities on which federal taxes are imposed. Then, to project revenues, the agency applies the appropriate tax rates—including the effects of changes to tax provisions as scheduled under current law—to its projection of taxable activities, which reflects the macroeconomic projections related to each activity. CBO models each tax source separately and projects total revenues by summing the projections of the separate sources.

How Does CBO Project Spending and Revenues?

CBO’s spending and revenue projections are estimated separately and then combined to project annual deficits or surpluses, calculate net outlays for interest, and project various measures of debt.

Projecting Mandatory Spending

CBO’s baseline projections for the accounts and subaccounts associated with mandatory programs can range from a million dollars per year for smaller programs to hundreds of billions of dollars per year for programs like Medicare and Social Security. In developing those projections, analysts must account for each program’s characteristics and complexities and incorporate current information related to the program.

Because of the diversity of mandatory programs, analysts gather and analyze data from many sources. For example, projections of spending on Medicare account for the age of beneficiaries and for the eligibility, coverage, and payment rules of Medicare’s benefit programs, along with Medicare’s interactions with Medicaid and other federal benefit programs. Projections of Social Security benefits account for the number of eligible people, the ages at which they typically claim benefits, and expected wage and price inflation, among other factors. Projections for student loan and housing programs account for default rates, and projections for crop insurance account for the number of acres planted with a given crop.

Projections of mandatory spending also must account for the effects of changes to programs and activities that result from previously enacted legislation. In addition, when applicable, projections of spending on certain mandatory programs also must account for sequestration, a legal process by which previously provided spending authority is canceled. 7

To project spending on military retirement benefits, for example, CBO’s analysts follow a three-step process:

- Estimate the number of retirees and survivors (surviving spouses and children) over the projection period. That estimate takes into account the actual caseload, by age, in the most recently completed fiscal year, projected retirements over the next decade based on the military force structure, and projected new survivor beneficiaries based on both the share of retirees electing to purchase survivor benefits and retirees’ mortality rates.

- Estimate the average net payment amount for retirees and survivors. That estimate reflects the actual gross payment amounts and offsets from the most recently completed fiscal year, the most recent cost-of-living increase provided to military retirees and pay increase provided to service members, and CBO’s latest projections of inflation from the economic forecast. Payments to military retirees could be reduced if retirees also received disability benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Those reductions are calculated using data about the receipt of benefits provided by the department, along with CBO’s projections of trends for disability compensation.

- Build in adjustments to account for program rules that would cause changes to spending. Those adjustments include accounting for the timing of the disbursement of retirement payments, which can vary from month to month and from year to year.

Projecting Discretionary Spending

Analysts typically begin their projections for discretionary spending accounts with the most recent appropriation. They then apply the appropriate inflation rate, identify the percentage of an appropriation that will be spent in the current year and each subsequent year on the basis of historical spending patterns and experience from the most recent fiscal year, and estimate when the appropriated amounts still available from previous years will be spent (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Spending Projections for a Sample Discretionary Account

Millions of Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office.

Numbers may not add up to totals because of rounding.

Budget authority is the authority provided by federal law to incur financial obligations that will result in immediate or future outlays of federal funds.

Budget authority in Year 1 is the amount appropriated in the current year.

Budget authority for Years 2 through 5 is the amount in Year 1, inflated using the appropriate inflators from the macroeconomic forecast.

Budget authority in each year is spent at the estimated rate for each account.

Outlays for each year are a combination of spending from budget authority that was provided in previous years (prior-year spending) and from the budget authority for the current year (new outlays).

n.a. = not applicable.

Because funding for personnel must be inflated at a different rate than funding for other purposes, inflation rates are weighted by the expected percentage of funding to be used to pay salaries and benefits and the percentage to be used for all other purposes in each account. The time it takes to spend the projected funding depends on the purpose for or conditions under which the money is provided. Funds from accounts that cover mainly salaries and expenses are spent more quickly (for example, 80 percent in the first year and 20 percent in the second), whereas accounts that fund construction projects, for example, often have longer, slower rates of spending (for example, 10 percent the first year, 25 percent in the second and third years, and less than 20 percent in subsequent years).

Finally, analysts research recent activities funded by appropriations and study economic and other trends that would affect projections of outlays.

In years for which caps on discretionary spending have been imposed (such as by the Budget Control Act of 2011), after account-level projections of discretionary spending are finalized, the total amount of budget authority is reduced to account for those caps.

Projecting Net Interest Costs

When they estimate net interest spending, analysts use a model that first incorporates each outstanding Treasury security, including its principal amount, time to maturity, and the interest rate that applies to it. The model then integrates projections of future deficits and other financing obligations, CBO’s forecast for interest rates, and judgments about the mix—or type—of securities the Treasury will issue to meet the resulting borrowing needs.8

Estimates of net interest costs rely on two critical factors—federal debt and interest rates:

- The stock of federal debt at the beginning of a projection period and the additional debt generated during the projection period (mostly the amount by which annual government spending exceeds annual revenues) substantially determine amounts of annual borrowing.

- Estimates of interest rates largely determine the amounts the Treasury would pay on outstanding debt.

To a lesser extent, interest costs also are sensitive to the mix of securities sold by the Treasury. In addition to projecting primary deficits—that is, deficits excluding net interest costs—and interest rates, CBO must project the types of debt that the Treasury might issue to finance annual deficits. The Treasury can select the characteristics of the debt it issues—for example, the time to maturity, whether interest rates are fixed or floating, and whether the interest payments include an adjustment for inflation (as they do for Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, for example). Those factors also are reflected in baseline estimates of net interest outlays.

The Deficit Control Act requires that CBO project spending, revenues, and deficits independently of the debt limit, which is the maximum amount of debt—specified by law—that the Treasury can issue to the public or to other federal agencies. Nevertheless, the debt limit has practical effects because once that limit is reached, the Treasury cannot issue additional debt that would increase the amount outstanding.

Compiling a Database of Spending Projections

As the spending projections are completed, they are compiled in a database that lists and codes each account to identify several characteristics, including the category of spending (for example, whether the spending is considered mandatory or discretionary); the committees of jurisdiction; whether the funding is designated as an emergency requirement; and whether the account is subject to sequestration. The database allows CBO to create, manage, and compare a variety of data sets and to provide detailed reports to the Congress. In addition to the baseline projections, the database includes information about the analyses of the President’s annual budget request as well as historical data from the Administration on past budget authority and outlays for each account.

Projecting Revenues

CBO’s analysts project revenues from various sources. The model used for each source depends on the information available. In some cases—for individual income taxes, for example—microsimulation modeling suggests how individual taxpayers would respond to current tax provisions. In other cases—for gasoline taxes, for example—activity is modeled in the aggregate.

The microsimulation model for individual income taxes starts with databases of information about individuals or households, including a sample of tax returns prepared by the Internal Revenue Service. On the basis of those inputs, CBO uses the model to project federal revenues from income taxes and payroll taxes. The agency also uses its demographic projections to account for changes in the number of taxpayers and in the demographic composition of that group, and it uses tax data to account for the kinds of income people receive or the wealth they accrue.9

To simulate conditions in a projection year using the database of tax returns or other information from an earlier year, CBO accounts for projected changes in the number of returns and in the amount of income, deductions, or other important information from sample returns. That process involves changing the weights in the sample—the total number of tax returns that each sample return represents—and income, wealth, or other measures of economic activity for each return. In CBO’s projections, wages and salaries are estimated to increase faster for higher-income taxpayers than for lower-income ones, but the distribution of most income sources among all taxpayers remains constant and grows at rates that are consistent with the economic forecast.

Aggregate-based modeling for other revenue sources starts with data on total economic activity, such as the total tax base on which a particular excise tax is applied or corporate profits for the economy as a whole as measured in the NIPAs. CBO projects the aggregate tax base and determines the relevant tax rate for each revenue source. The aggregate-based approach is more appropriate for projecting revenues from sources for which the distribution of economic activity among taxpayers is less important—from excise taxes, for example, because the same tax rate generally applies to similar production and consumption, or from corporate income because it generally is taxed at a uniform rate.

For example, when CBO’s analysts project receipts from the gasoline excise tax, they start with the most recent data on gasoline taxes and divide those amounts of revenues by the federal tax rate to find the total number of gallons taxed. They then project gasoline consumption by accounting for expected changes in the number of miles that people drive; for legislated increases in fuel economy standards, which would reduce gasoline consumption per mile traveled; and for projected changes in the cost of fuel, which are part of CBO’s economic forecast.

Despite their differences, the microsimulation and aggregate-based approaches have several elements in common:

- CBO’s economic forecasts are critical inputs to both models.

- Both types of models are structured on the basis of tax years, which generally conform to calendar years, so they produce estimates of taxes owed by taxpayers for a particular tax year. To convert tax year projections of taxes owed to fiscal year projections of tax payments, CBO accounts for the rules that govern withholding, estimated payments, and historical payment patterns. That way, the agency can project how much of what is owed for a particular tax year will be paid in the same fiscal year and how much will be paid in the next or later fiscal years.

- The models’ results must be adjusted to reflect the effects of scheduled changes in tax law.

How Does CBO Ensure Consistency Between Its Baseline Projections and Its Economic Forecast?

All of the agency’s reports, estimates, and analyses are developed within an analytical framework that requires consistency among them; thus, it is essential that CBO’s projections of spending and revenues are consistent with its economic forecast (and vice versa). That framework for developing information that is interdependent and based on a common set of assumptions helps ensure that the agency’s assessments are objective and analytically consistent.

CBO’s analysis of the nation’s economic outlook depends in part on fiscal policy. The amount by which revenues and outlays differ, for example, affects short-term demand and the economy’s long-term capacity to produce goods and services.

Although the agency’s macroeconomic models are not automatically linked to its revenue and spending models, the results from the models and the various projection methods are determined jointly in an iterative process. First, results from revenue and spending models are incorporated into CBO’s macroeconomic models. The resulting economic forecast is then incorporated into existing revenue and spending models, which, in turn, produce new budget projections that are again fed back into the agency’s macroeconomic models. The number of such iterations can vary, depending in part on the extent of change since the previous baseline. That process helps ensure that each baseline reflects the interactions between the economy and fiscal policy under current law.

Does CBO Assess the Accuracy of Its Baseline Projections?

CBO periodically reports to the Congress about the accuracy of its projections.10 After each fiscal year has ended, the agency reviews its projections of federal revenues and outlays and the government’s budget deficit and compares them with actual budgetary outcomes for that year. CBO seeks to improve the accuracy of its work by assessing the quality of its projections and identifying the factors that might have led to under- or overestimates of particular categories of federal revenues and outlays.

In addition, CBO undertakes separate analyses to attempt to improve certain elements of its projections. For example, the agency analyzed the extent to which certain international tax avoidance strategies could lead to changes in corporate income tax receipts, which led it to reduce its projection of the amount of corporate profits subject to the corporate tax.11

CBO’s internal review process also stresses its assessment of the quality of past projections to identify opportunities to refine methods and improve the accuracy of future projections.

What Information Does CBO Release Along With Its Baseline Projections?

Each year, The Budget and Economic Outlook and its updates describe the main factors that influence baseline projections of spending and revenues.12 CBO also often provides supplementary information to accompany the baseline projections. Such information includes estimates of the sensitivity of the results to alternative economic projections and the budgetary effects of mandatory spending that is assumed to continue throughout the baseline period because of the provisions of law that govern how the baseline is developed. In addition, to assist policymakers who may hold differing views about the most useful benchmark projections for discretionary spending, CBO’s reports sometimes show budgetary effects under alternative policy assumptions—for example, presenting projections in which discretionary appropriations are frozen at the amounts provided in the current fiscal year.

CBO also regularly provides explanations of how and why economic and budgetary projections have changed since earlier reporting. It posts supplemental materials, including various spreadsheets that show budget authority and outlays for every account in the baseline. Supplemental tables with more detailed information on larger, more complicated programs and accounts also are posted.13

For revenue projections, the supplemental data typically include information about the components of projected revenues from payroll and excise taxes; details on the components of individual income and calculations of tax liabilities; details on projected individual capital gains realizations and the resulting tax receipts; information about the relationship between profits in national income and income subject to the corporate tax; and estimates, provided by JCT, of changes in baseline projections that would occur if different expiring tax provisions were instead assumed to be extended permanently.

1. Robert Arnold, How CBO Produces Its 10-Year Economic Forecast, Working Paper 2018-02 (Congressional Budget Office, February 2018), www.cbo.gov/publication/53537.

2. Mandatory, or direct, spending is governed by statutory criteria and usually not constrained by the annual appropriation process. CBO provides cost estimates to assist the Congress in determining the budgetary effects of legislation. For more information, see Congressional Budget Office, CBO Describes Its Cost-Estimating Process (April 2023), www.cbo.gov/publication/59003. For more on the federal budget process and budget enforcement procedures, see Congressional Budget Office, The Statutory Pay-As-You Go Act and the Role of the Congress (August 18, 2020), www.cbo.gov/publication/56506, and Cash and Accrual Measures in Federal Budgeting (January 2018), Box 1, p. 4, www.cbo.gov/publication/53461.

3. Congressional Budget Office, “Major Recurring Reports: Long-Term Budget Outlook,” https://tinyurl.com/3dvkuxa8, and “Major Recurring Reports: Long-Term Projections for Social Security,” https://tinyurl.com/y8ym8dwy.

4. One exception is for projections in which costs depend on whether some uncertain variable—for example, the price of crude oil or an inflation or unemployment rate—reaches a specified trigger level. In those cases, CBO considers a range of possible outcomes and their associated probabilities. CBO refers to such trigger provisions as one-sided bets because they affect costs on only one side of the trigger value. See Congressional Budget Office, Estimating the Cost of One-Sided Bets: How CBO Analyzes the Effects of Spending Triggers (October 2020), www.cbo.gov/publication/56698.

5. Subsequent amendments to the Budget Act specify the methods CBO uses to estimate the budgetary effects of federal credit programs.

6. Congressional Budget Office, Improving CBO’s Methodology for Projecting Individual Income Tax Revenues (February 2011), www.cbo.gov/publication/22007.

7. For more information on sequestration, see Congressional Budget Office, “Sequestration,” www.cbo.gov/topics/budget/sequestration.

8. Congressional Budget Office, Federal Net Interest Costs: A Primer (December 2020), www.cbo.gov/publication/56780. For a discussion of CBO’s analysis of federal debt, see Congressional Budget Office, Federal Debt: A Primer (March 2020), www.cbo.gov/publication/56165.

9. Congressional Budget Office, “Budget and Economic Data: Demographic Projections,” https://tinyurl.com/22n23795.

10. For a discussion of CBO’s assessments of its baseline projections and economic forecasts, see Congressional Budget Office, “Accuracy of Budget Projections,” www.cbo.gov/topics/budget/accuracy-projections, and CBO’s Economic Forecasting Record: 2021 Update (December 2021), www.cbo.gov/publication/57579.

11. Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of Corporate Inversions (September 2017), www.cbo.gov/publication/53093.

12. Congressional Budget Office, “Major Recurring Reports: Budget and Economic Outlook and Updates,” https://tinyurl.com/28cx7cd7.

13. Congressional Budget Office, “Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs,” www.cbo.gov/about/products/baseline-projections-selected-programs, and “Budget and Economic Data,” www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data.

Emily Stern prepared this document with guidance from Theresa Gullo, John McClelland, and Sam Papenfuss. Christina Hawley Anthony, Robert Arnold, Kathleen FitzGerald, Ann E. Futrell, Avi Lerner, Paul Masi, David Newman, and Dan Ready provided comments.

Mark Hadley, Jeffrey Kling, and Robert Sunshine reviewed the primer. Scott Craver edited it, and Jorge Salazar created the graphics and prepared the text for publication. The primer is available at www.cbo.gov/publication/58916.

CBO seeks feedback to make its work as useful as possible. Please send comments to communications@cbo.gov.