Last week CBO released its annual summer update of its budget and economic outlook. The blog posting for that release focused on CBO’s overall economic and budget projections, so we didn’t have a chance to highlight specific aspects of those projections that may be interesting to some people. This week we’d like to summarize three such aspects: the amount of discretionary spending that will occur over the coming decade under current law, the estimated impact of fiscal policy on economic growth during the next few years, and persistent effects of the recent recession on potential output (the amount of output that corresponds to a high rate of use of labor and capital). We’ll begin today with discretionary spending (which is discussed on pages 17 to 23 of the report).

Projected Discretionary Outlays

CBO’s baseline projection incorporates the caps placed on discretionary budget authority (the authority provided by law to incur financial obligations, which eventually result in outlays) for 2012 through 2021 by the Budget Control Act. Discretionary budget authority subject to the caps will be limited to $1.043 trillion in 2012 and $1.047 trillion in 2013, and growth will be restricted to about 2 percent per year after that, with discretionary budget authority reaching a maximum of $1.234 trillion in 2021. Those caps do not constrain appropriations for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq or for similar activities, sometimes known as overseas contingency operations. (The caps also can be adjusted each fiscal year to account for some funding designated for emergencies and for disaster relief.) In projecting funding for overseas contingency operations, CBO followed long-standing procedures governing baseline projections by assuming that appropriations would equal the funding provided for 2011 with adjustments for inflation.

With those amounts included, total budget authority for discretionary programs would rise from $1.20 trillion in 2012 to $1.43 trillion in 2021. (Those projections do not account for any changes in discretionary appropriations that could occur as a result of provisions of the Budget Control Act related to the deficit reduction committee because CBO cannot predict what those changes might be.) Appropriations of those amounts will mean reductions in the real resources available for the government’s programs. If discretionary budget authority was allowed to grow at the rate of inflation, without the constraint on nonwar funding imposed by the caps, such authority would be about 4 percent higher in 2012 and 8 percent higher in 2021.

Total Discretionary Budget Authority Excluding War Funding

Even with such adjustments for inflation, however, appropriations could be insufficient to continue current policies over the 2012–2021 period. For example, the cost of veterans’ health benefits—assuming current enrollment rules remain unchanged—is projected by CBO (in the report Potential Costs of Veterans’ Health Care) to rise more rapidly than inflation and thus to exceed the budget authority calculated simply by extrapolating the current year’s appropriations at the projected rate of inflation. Similarly, maintaining current award amounts for Pell grants would require funding above what would be shown in a projection based on inflating 2011 appropriations. Moreover, if budget authority for defense programs grew at the rate of inflation, that amount of funding would be insufficient to pay for the Future Years Defense Program put forward in February 2011 by the Department of Defense. According to CBO’s calculations (in the report Long-Term Implications of the 2012 Future Years Defense Program), over the period from 2012 to 2021, defense funding that would be needed to implement that plan would exceed by about $480 billion the amounts projected by assuming that current budget authority increased at the rate of inflation.

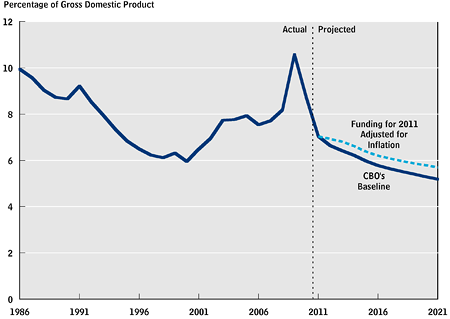

Total discretionary outlays in CBO’s baseline are projected to decline in 2012 and 2013, and to grow slowly thereafter, exhibiting an average annual increase of 1.2 percent from 2013 through 2021—less than the 1.8 percent rate of growth that would be projected if all discretionary appropriations grew at the rate of inflation. (Such outlays increased by 8.9 percent in 2010, and by an annual average of 8.0 percent between 2000 and 2009.) As a result, in CBO’s baseline, discretionary outlays decline from 9.0 percent of GDP in 2011 to 6.1 percent of GDP in 2021, a share of the total economy roughly equal to that for discretionary outlays from 1998 through 2001 but well below the 8.7 percent average over the past 40 years.

Illustrative Paths of Defense and Nondefense Budget Authority

The Budget Control Act sets separate caps on “security” and “nonsecurity” funding for 2012 and 2013. The act sets overall caps only on total appropriations for 2014 to 2021. The categories specified for 2012 and 2013 do not correspond to the split of spending into defense and nondefense components that CBO normally reports, and the caps could be met through many combinations of defense and nondefense appropriations.

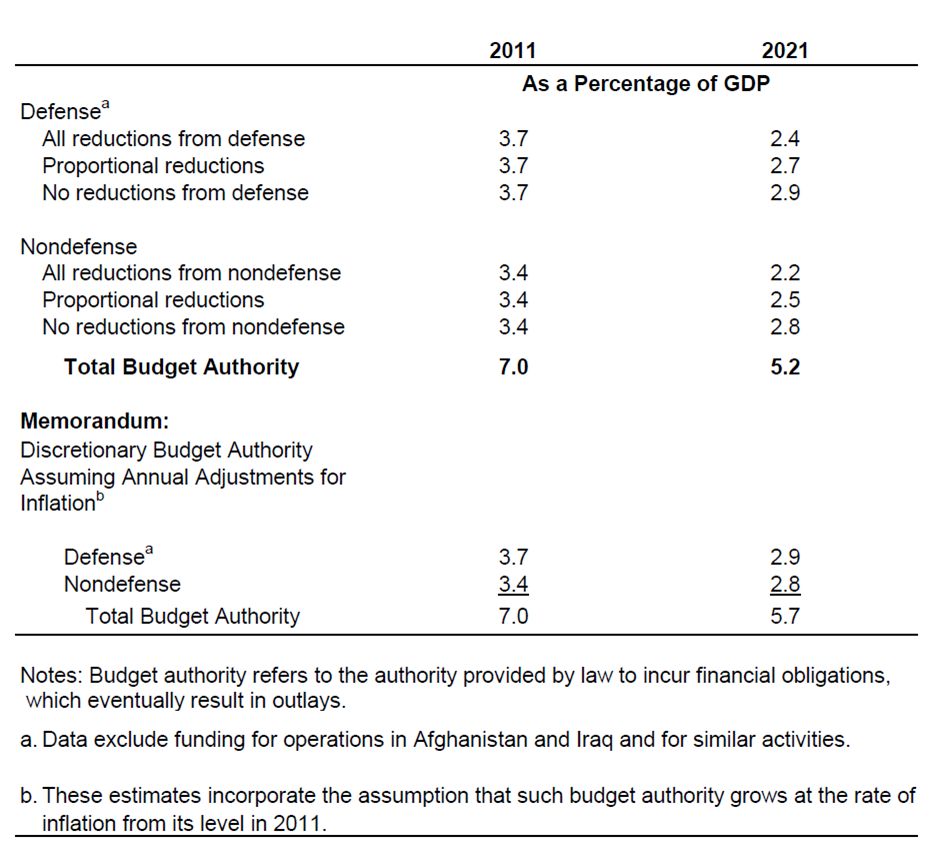

To illustrate the potential impact of the discretionary caps, CBO has projected defense and nondefense appropriations under a few different assumptions about how savings would be obtained. For example, defense and nondefense appropriations might be cut proportionately, relative to the funding that would be necessary to keep pace with inflation, in order to keep total discretionary funding within the caps. In that case, funding for each category would be about 1 percentage point of GDP lower in 2021 than estimated for this year (see below), a decline of more than one-fourth. Funding for defense purposes in 2021 would represent 2.7 percent of GDP; by comparison, annual funding for defense has averaged 4.2 percent of GDP during the past decade. Nondefense funding in 2021 would represent 2.5 percent of GDP; by comparison, such funding has averaged 3.7 percent of GDP during the past decade.

Illustrative Paths for Discretionary Budget Authority Subject to the Caps Set in the Budget Control Act of 2011

Alternatively, nearly all reductions in appropriations—relative to the funding that would be necessary to keep pace with inflation—that would be necessary to meet the discretionary caps could come from defense activities. In that case, budget authority for defense programs that are not directly related to operations in Afghanistan and Iraq would drop from 3.7 percent of GDP in 2011 to 2.4 percent of GDP in 2021, one-third less than current defense appropriations relative to the projected size of the economy. With that degree of restraint in defense funding, budget authority for nondefense programs could grow at close to the rate of inflation. Still, such funding would fall from 3.4 percent of GDP this year to 2.8 percent of GDP 10 years from now.

As another possibility, defense funding could grow at the rate of inflation and all reductions needed to meet the caps could come from nondefense programs. In that case, CBO projects, defense appropriations would total 2.9 percent of GDP in 2021—still a decline of more than 20 percent as a percentage of GDP compared with funding in 2011—and nondefense appropriations would be 2.2 percent of GDP, a drop of more than one-third relative to the projected size of the economy.