Notes

Notes

Unless this report indicates otherwise, all years referred to are federal fiscal years, which run from October 1 to September 30 and are designated by the calendar year in which they end. Numbers in the text, figures, and tables may not add up to totals because of rounding. Previous editions of this report, which CBO publishes annually, are available at https://go.usa.gov/xEnE6.

This report describes the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the costs and budgetary consequences through 2031 of current plans for the Department of Defense (DoD). Ordinarily, CBO would have based its projections of long-term costs on DoD’s 2022 Future Years Defense Program (FYDP), which would have covered fiscal years 2022 to 2026. However, as is common when a new Administration submits its first budget request, DoD did not release a 2022 FYDP. Therefore, the report draws from the fiscal year 2022 budget request submitted by the Biden Administration, other documents and statements published by the Administration, and the 2021 FYDP (the most recent five-year plan released by DoD).

The Administration’s 2022 budget request calls for $715 billion in funding for DoD. In real terms—that is, with adjustments to remove the effects of inflation—the funding request is 1.5 percent less than the total amount provided for 2021 and 1.0 percent less than the amount that would have been requested for 2022 under the Trump Administration’s final (2021) FYDP.1

Almost two-thirds of the request is for operation and support ($292 billion for operation and maintenance and $167 billion for military personnel), and about one-third is for acquisition ($134 billion for procurement and $112 billion for research, development, test, and evaluation). The remaining $9.8 billion is for infrastructure ($8.4 billion for military construction and $1.4 billion for family housing).

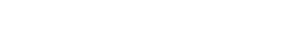

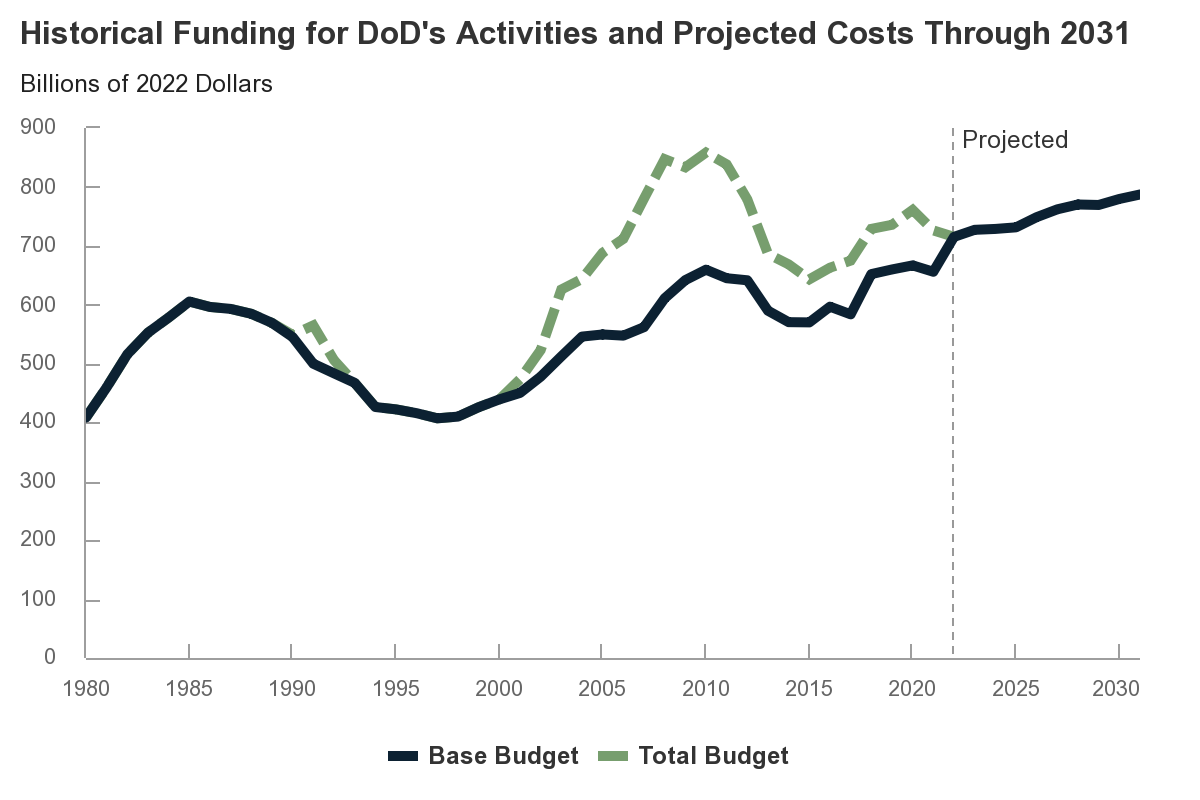

For the years after 2022, CBO projects that DoD’s costs would steadily increase so that, in 2031, the department’s budget (in 2022 dollars) would reach $787 billion, about 10 percent more than the amount proposed in the 2022 budget (see Figure 1). Several factors would contribute to those rising costs, including the following:

- Continued growth in the costs of compensation for service members and DoD’s civilian employees, which would account for 24 percent of the increase;

- Continued growth in other costs to operate and maintain the force, which would account for 35 percent; and

- Increased spending on new, advanced military equipment and weapons (largely as a result of DoD’s shift in focus from counterinsurgency operations to potential conflicts with technologically advanced militaries), which would account for 39 percent.

Figure 1.

Historical Funding for DoD’s Activities and Projected Costs Through 2031

Billions of 2022 Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57541#data.

DoD’s total budget consists of the following: base-budget funding that is appropriated for normal, peacetime operations and other activities that are anticipated during the regular budgeting process; and supplemental funding that is appropriated for overseas contingency operations and emergencies such as natural disasters. Starting in 2022, CBO shows only base-budget funding because in that year DoD began requesting funding for the anticipated costs of overseas contingency operations as part of its regular appropriations.

DoD = Department of Defense.

Although the Administration’s request for 2022 is about $7 billion less than the amount that was planned for 2022 in the 2021 FYDP, the cumulative costs through 2031 under the projections presented here would be about the same as the costs CBO had projected for the 2022–2031 period in its analysis of that earlier FYDP.2

In a departure from its practice for more than a decade, DoD did not split its 2022 request into two components: a base budget and funding for overseas contingency operations (OCO). The base budget was intended to fund normal, peacetime operations and other activities anticipated during the regular budgeting process, and OCO funding was intended for major overseas operations (primarily the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq). However, appropriations for OCO were also used to fund base-budget activities because the base budget was capped under the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA). (Funding provided for OCO and for emergencies such as natural disasters was not subject to those caps.) There was no need to separate base-budget costs from anticipated OCO costs in the 2022 request because fiscal year 2021 was the final year in which the base budget was subject to caps under the BCA (see Box 1). Of the amount requested for 2022, DoD identified $42 billion in funding for OCO, including both direct costs for current conflicts and enduring costs for other activities previously included in OCO.

Box 1.

DoD’s Base-Budget and OCO Costs Under the Budget Control Act: 2013 to 2021

Most of the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) funding in recent years was subject to the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), which established caps on most discretionary appropriations—including those for national defense—through 2021. (Specific caps on spending for national defense, budget function 050, went into effect in 2013.)1 However, the caps applied only to the base budget, which was intended to fund normal, peacetime operations and other activities anticipated during the regular budgeting process. The caps did not apply to appropriations designated for overseas contingency operations (OCO) or as emergency requirements, such as DoD’s relief activities after a natural disaster. The BCA’s limits were increased five times: by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 and the Bipartisan Budget Acts of 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2019. Together, those actions eased the constraints on funding each year from 2013 to 2021. In total, relief from the BCA’s caps amounted to $466 billion (in 2022 dollars) over that period.

Even with those increases in the caps, DoD’s cumulative base-budget funding from 2013 to 2021 was about $700 billion less (in 2022 dollars) than the costs that were anticipated by the 2012 Future Years Defense Program (FYDP)—the last one prepared before the law’s enactment—and the Congressional Budget Office’s extension of that plan through 2021 (see the figure). That corresponds to a reduction of about 11 percent.

However, some base-budget costs were allocated to OCO over the years. All told, the cumulative funding in DoD’s total budgets (the base budget plus OCO and emergency funding) for 2013 to 2021 was about the same as the amount projected for the base budget in the 2012 FYDP.

Paying for base-budget activities with OCO funding became explicit in the 2015 budget, when so-called OCO for Base Requirements were first identified as a subset of the OCO budget. From 2015 to 2021, DoD identified $75 billion as OCO for Base Requirements. That practice may also have been occurring in earlier years, but those costs were not reported in a separate category in budget documents. Too many factors contribute to yearly changes in war costs to make a meaningful estimate of how much OCO funding might have been more appropriately allocated to the base budget.2

Now that the BCA has lapsed, DoD is no longer separating anticipated costs for overseas contingency activities from base-budget costs in its regular funding request to the Congress. However, DoD may still request supplemental or emergency funding if unanticipated costs arise during the fiscal year.

1. Appropriations for activities in budget function 050 include those for DoD, the Department of Energy’s nuclear weapons activities, and a host of smaller defense-related activities in other departments and agencies.

2. For a detailed analysis of OCO budgets through 2019, see Congressional Budget Office, Funding for Overseas Contingency Operations and Its Impact on Defense Spending (October 2018), www.cbo.gov/publication/54219.

The Basis of CBO’s Projections of the New Administration’s Plans

CBO usually bases its long-term projections of defense costs on the FYDP that DoD prepares each year in conjunction with its budget request. The FYDP describes planned changes in force structure, outlines schedules for anticipated major purchases of weapons, and provides estimates of costs for the ensuing five years. Because a five-year plan was not available this year, CBO based the projections in this report on the Administration’s 2022 budget request for DoD and other official documents and statements, such as the 2021 FYDP (if more recent data were not available) and the Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, which was released by the Administration in March 2021.3 (The Administration is in the process of developing a new National Security Strategy.)

Unlike the Trump Administration, which entered office in 2017 with the stated intention of expanding the military, the Biden Administration has not articulated plans to substantially change the force structure. (Force structure is the number of major combat units, such as infantry brigades, battle force ships, and aircraft squadrons.) Therefore, CBO’s projections do not incorporate changes in the size of the force over the next 10 years. CBO’s projections do reflect the assumption that the previous Administration’s emphasis on maintaining the readiness of today’s force would be carried forward. To project costs for developing and fielding new weapons, CBO started with DoD’s five-year estimates of costs and schedules in its 2021 FYDP and adjusted those plans to align with the department’s 2022 budget request.

CBO’s projections of DoD’s costs through 2031 are based on plans as they stood when DoD was finalizing them in the early months of 2021. Because the current Administration had been in office only a short time, considerable uncertainty exists about how those plans might evolve. Factors such as international events, fiscal considerations, and Congressional decisions could lead to changes. Even if DoD’s plans generally remained unchanged, many program-level policies that underlie DoD’s estimates of its costs might not come to pass. For those reasons, CBO’s projections should not be viewed as predictions of future funding for DoD; rather, the projections are estimates of the costs of executing the department’s plans as they stood at the time the Administration submitted its 2022 budget request.

Projected Costs of DoD’s Plans Through 2031

CBO’s projections began with an examination of DoD’s estimates of costs and force structure for 2022. As much as possible, CBO’s projections of DoD’s costs over the 2023–2031 period are based not only on costs underlying the Administration’s 2022 request but also on the following: policies articulated in official documents and testimony; current laws regarding military compensation; and the long-term acquisition plans that DoD publishes in its Selected Acquisition Reports and other official documents (such as the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan). When no estimates of DoD’s costs were available, CBO based its projections on prices and compensation trends in the general economy. (For a summary of CBO’s projection methods for each part of DoD’s budget, see Table 1.)

Nearly all of DoD’s funding is provided in seven appropriation titles: military personnel; operation and maintenance (O&M); procurement; research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E); military construction; family housing; and revolving and management funds. In analyzing the cost of DoD’s plans, CBO organized those seven appropriations into three broader categories according to the types of activities they fund: operation and support (O&S), acquisition, and infrastructure. CBO projects that costs will increase for all three categories.

Operation and Support

O&S funding is the sum of appropriations for military personnel, O&M, and revolving and management funds. CBO folded the relatively small amounts appropriated for revolving and management funds into its projections of the O&M appropriation because they involve similar activities. O&S appropriations are used to compensate all uniformed (and most civilian) personnel in the Department of Defense, to pay most costs of the Military Health System (MHS), and to fund most day-to-day military operations.

DoD’s 2022 Budget Request for O&S. For 2022, DoD requested $460 billion in funding for O&S, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the department’s budget request: $167 billion for military personnel and $292 billion for O&M. The amount requested for O&S in 2022 is about the same as the amount provided for 2021 and $6.3 billion (or 1 percent) less than the amount planned for 2022 in the 2021 FYDP.

Projections of O&S Costs Through 2031. Beyond 2022, CBO’s projections of costs for O&S are based on DoD’s 2022 budget request, projections of economywide factors such as labor costs, and historical trends in O&M costs per active-duty service member.

CBO’s analysis indicates that, after 2022, O&S costs in DoD’s budget would increase at an average annual rate of 1.0 percent above the rate of inflation, reaching $502 billion in 2031 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

DoD’s Costs for Operation and Support, Acquisition, and Infrastructure, 1980 to 2031

Billions of 2022 Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57541#data.

DoD’s total budget consists of the following: base-budget funding that is appropriated for normal, peacetime operations and other activities that are anticipated during the regular budgeting process; and supplemental funding that is appropriated for overseas contingency operations and emergencies such as natural disasters. Starting in 2022, CBO shows only base-budget funding because in that year DoD began requesting funding for the anticipated costs of overseas contingency operations as part of its regular appropriations.

Funding for operation and support is the sum of the appropriations for military personnel, operation and maintenance, and revolving and management funds. Acquisition funding is the sum of the appropriations for procurement and for research, development, test, and evaluation. Infrastructure funding is the sum of the appropriations for military construction and family housing.

DoD = Department of Defense.

CBO based its projections of DoD’s O&S costs on the anticipated growth in three categories of costs:

- Compensation, which consists of pay and cash benefits for military personnel and DoD’s civilian employees as well as the costs of retirement benefits. Those costs fall under the appropriations for military personnel and O&M (for civilian employees).

- The Military Health System, which provides medical care for military personnel, military retirees, and their families. Those costs are funded primarily by the appropriations for military personnel and O&M.

- Other O&M, which covers costs such as those for base operations, fuel, depot maintenance, and spare parts. Those costs fall entirely under the appropriation for O&M.4

For compensation, CBO’s projections for the 2023–2031 period reflect the assumption that military and civilian pay raises would equal CBO’s forecast of growth in the employment cost index (ECI), a measure developed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics that tracks the change in compensation per employee hour worked. Current law sets military pay raises equal to the growth in the ECI unless the Congress or the President takes action to provide different amounts. CBO also projects that civilian pay raises would maintain parity with military pay raises. Under that forecast, compensation costs would increase at an average annual rate of 0.7 percent above the rate of inflation, for a cumulative real increase of 7 percent by 2031 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

DoD’s Operation and Support Costs, by Appropriation Title and as Categorized by CBO

Billions of 2022 Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57541#data.

Funding for operation and support is the sum of the appropriations for military personnel, operation and maintenance, and revolving and management funds.

DoD = Department of Defense; MHS = Military Health System; O&M = operation and maintenance.

a. CBO included the relatively small amount in DoD’s budget for revolving and management funds with the O&M appropriation because those two titles involve similar activities.

b. Compensation consists of pay, cash benefits, and accrual payments for retirement benefits. For civilians, it also includes DoD’s contributions for health insurance.

c. The amounts shown here do not include compensation for civilian personnel funded from accounts other than O&M.

d. These amounts do not include spending for the MHS in accounts other than operation and support. The amounts shown for military and civilian pay in the MHS are also included in the compensation category.

Military health care costs have almost doubled in real terms over the past 20 years (see Figure 3). That increase has resulted from expansions of the benefits offered—in particular, the addition of TRICARE for Life benefits for military retirees and their families—as well as from general increases in the cost of health care in the United States. CBO projects that annual military health care costs will continue to increase at a rate consistent with its projections of nationwide health care costs but with adjustments to account for the unique aspects of the MHS. Under that assumption, military health care costs would rise at an average annual rate of 1.4 percent in real terms, from $52 billion in 2022 to $59 billion in 2031.5

Figure 3.

Costs of the Military Health System, 1980 to 2031

Billions of 2022 Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57541#data.

Before 2001, pharmaceutical costs were not identified separately but were embedded in the costs of two categories: “Purchased Care and Contracts” and “Direct Care and Administration.” Since 2001, most pharmaceutical costs have been identified separately, but some are still embedded in the category “TRICARE for Life Accrual Payments.”

The amounts shown here do not include spending for the Military Health System in accounts other than military personnel and operation and maintenance.

In its projections of costs for the category of spending classified as “other O&M,” CBO estimated that costs would increase faster than inflation, consistent with long-standing trends.6 Between 1980 and 2021, DoD’s other O&M costs have more than tripled in real terms after adjusting for changes in the size of the military. Because it is not practical to make individual estimates of the cost of the thousands of activities that other O&M comprises, CBO’s projections reflect overall cost growth that is consistent with that historical trend. The result is an average annual increase of 1.2 percent in real terms, which would cause annual costs for other O&M to increase by $20 billion (or 11 percent) from 2022 to 2031.

Comparison With the 2021 FYDP. Costs for O&S in DoD’s 2022 budget request are $6.3 billion (or 1.4 percent) less than the amount planned for 2022 in the 2021 FYDP. Of that decrease, $5.3 billion is in O&M, and $1 billion is in military compensation. The 2022 request incorporated a slightly larger military pay raise for 2022 than was reflected in the 2021 FYDP, but the planned number of military personnel is slightly lower.

CBO’s current projection of cumulative costs for O&S is 1.4 percent higher than its September 2020 projection for the 2022–2031 period, which was based on the 2021 FYDP. The lower costs in 2022 under the current request would be offset by faster rates of growth in costs for compensation, health care, and other O&M in subsequent years. Specifically, CBO’s earlier projections incorporated the slower growth rates that were reflected in the 2021 FYDP for 2022 to 2025 and the faster rates of growth that were based on the ECI, economywide health care costs, and historical costs of O&M for the years thereafter. In the absence of a 2022 FYDP, CBO used the faster growth rates for the entire 2022–2031 period in its current projections.

Acquisition

Acquisition funding comprises appropriations for procurement and RDT&E. That funding is used to develop and buy new weapon systems and other major equipment, upgrade or extend the service life of existing weapon systems, and support research on future weapon systems.

DoD’s 2022 Budget Request for Acquisition. For 2022, DoD requested $246 billion for acquisition: $134 billion for procurement and $112 billion for RDT&E. That amounted to about one-third of DoD’s total request. The amount requested for acquisition in 2022 was 5 percent ($12 billion) less than the amount provided for 2021 and less than 1 percent ($1.4 billion) more than the amount planned for 2022 in the 2021 FYDP.

Projections of Acquisition Costs Through 2031. For projections beyond 2022, CBO relied primarily on the acquisition cost data provided with DoD’s 2021 FYDP and other long-term plans such as Selected Acquisition Reports. CBO modified those prior-year plans to reflect actual appropriations for 2021, changes proposed in the 2022 budget request, and other, more recent documents such as the Navy’s fiscal year 2022 shipbuilding plan.

In CBO’s projections, DoD’s acquisition costs increase after 2022 at an average annual rate of 1.2 percent above the rate of inflation, reaching $273 billion in 2031 (see Figure 2). Procurement costs would be $40 billion higher in 2031 (a 3.0 percent annual increase, on average, over the 2022–2031 period) as purchases of new weapons, including several that are currently in development, increased. Although costs for RDT&E would fall to about $100 billion in 2031 (a 1.3 percent average annual decrease over the projection period), that amount would still be large by historical standards.

All three military departments—the Army, Navy (which includes the Marine Corps), and Air Force (which includes the Space Force)—would have higher acquisition costs in 2031, CBO projects.

- The increase for the Army—$3 billion, or nearly 9 percent—includes projected costs for new scout and transport helicopters and new ground-combat vehicles.

- The increase for the Navy—$16 billion, or nearly 20 percent—would account for more than half of DoD’s total increase (see Figure 4). Most of the increase in the Navy’s acquisition costs would be for shipbuilding to support plans to increase the size of the fleet (including the development and deployment of new unmanned ships) and to replace the Ohio class ballistic missile submarine fleet with the new Columbia class.

- The increase for the Air Force—$6 billion, or about 9 percent—includes costs for nuclear forces, such as the B-21 bomber and replacements for the Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile force, as well as continued purchases of fighters and advanced air-launched weapons.

Figure 4.

DoD’s Acquisition Costs, by Military Department, 2010 to 2031

Billions of 2022 Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/57541#data.

Acquisition funding is the sum of the appropriations for procurement and for research, development, test, and evaluation.

Funding shown for the Air Force does not include approximately $30 billion each year for classified activities not carried out by the department.

DoD = Department of Defense.

In addition, the defensewide appropriation, which funds organizations such as the defense agencies and Special Operations Command, would also be slightly larger in 2031.

CBO’s projections of acquisition costs are based on DoD’s cost and schedule estimates for major weapon system programs that are explicitly defined in published documents, such as Selected Acquisition Reports, or implicitly included in more general policy statements, such as those regarding the Air Force’s new bomber. However, CBO has observed that, historically, long-term acquisition costs can deviate from published plans, which can result in spending that is several percentage points higher than DoD’s estimates. Unexpected cost growth comes from several sources, including the following: overly optimistic development plans; unforeseen economic forces that increase the costs of materials and labor; unanticipated difficulties during development, manufacturing, or production; and decisions to accelerate production. Incorporating an estimate of cost growth based on historical experience raises projected acquisition costs by a total of $117 billion (or 4 percent) over the 2022–2031 period.7

Comparison With the 2021 FYDP. Costs for acquisition in the 2022 budget request are $1.4 billion higher than the amount planned for 2022 in the 2021 FYDP, an increase of less than 1 percent. Changes were larger within each of the components of acquisition, however: Costs for procurement decreased by $5.6 billion (or 4 percent), and costs for RDT&E increased by $7.0 billion (or 7 percent). Some of the decrease in procurement costs resulted from developmental delays. For example, the 2021 FYDP anticipated procurement of eight MH-139A helicopters in 2022, but those purchases have been deferred because of delays in the Federal Aviation Administration’s certification of the new aircraft. For other programs, DoD may have slowed purchases while it awaits the outcome of its national security review.

Because the Administration has not announced major changes in DoD’s acquisition plans, CBO projects little change in cumulative acquisition costs over the 2022–2031 period. Specifically, such costs are projected to be $23 billion higher than the costs that CBO projected on the basis of the 2021 FYDP, a change of less than 1 percent. Nevertheless, major changes resulting from the national security review are possible. Examples that have been discussed include reducing purchases of F-35 fighters and canceling plans to purchase new intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure funding is the sum of the appropriations for military construction and family housing. Those funds are used to build and renovate DoD’s facilities and to manage housing on military installations.

DoD’s 2022 Budget Request for Infrastructure. Requested appropriations for infrastructure total $9.8 billion for 2022, or less than 2 percent of the budget request. That is about $700 million more than the amount appropriated for 2021 but $1.8 billion less than the amount planned for 2022 in the 2021 FYDP.

Projections of Infrastructure Costs Through 2031. In CBO’s projections, DoD’s infrastructure costs increase by 8 percent, to $10.6 billion, in 2023—an amount that reflects the trend in DoD’s infrastructure costs since 1980. Thereafter, infrastructure costs are projected to steadily increase at an average annual rate of 1 percent, reaching $11.5 billion in 2031. (Such a steady increase represents an average trend; actual costs can vary from year to year because one or more large construction projects may significantly affect total costs in a specific year.) Although substantial on a percentage basis, the increase in infrastructure costs over the projection period would contribute only slightly to the growth in DoD’s total costs because infrastructure accounts for a small portion of the department’s total budget.

The increase that CBO projects for infrastructure costs over the 2023–2031 period reflects the expectation that construction costs would rise at a rate equal to that of the real cost of construction projects in the general economy; that rate is higher than the projected rate of inflation. CBO did not include the potential effects of a new round of the Base Realignment and Closure process.

Comparison With the 2021 FYDP. Costs for infrastructure in DoD’s 2022 budget request are $1.8 billion (or 16 percent) less than the amount planned for 2022 in the previous year’s FYDP. Over the entire 10-year period, however, CBO’s projections of infrastructure costs are about the same as the projections it based on DoD’s 2021 FYDP for 2023 to 2025. That is because infrastructure costs anticipated for those years in the 2021 FYDP were about 7 percent lower than historical averages. For the current projections, CBO applied the higher historical average starting with 2023, instead of 2026 (the first year beyond the period included in the 2021 FYDP).

1. To remove the effects of inflation, CBO used the gross domestic product price index from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Dollar amounts are expressed in 2022 dollars.

2. See Congressional Budget Office, Long-Term Implications of the 2021 Future Years Defense Program (September 2020), www.cbo.gov/publication/56526.

3. See President Joseph R. Biden Jr., Interim National Security Strategic Guidance (March 2, 2021), https://go.usa.gov/xMGxD.

4. A sum of the costs in CBO’s three categories would exceed total O&S funding because the cost of compensation for military and civilian personnel who work in the Military Health System would be counted twice: once in the compensation category and again in the MHS category. When discussing the categories in isolation, CBO includes those costs in both categories to present a more complete picture of each category’s costs; but CBO corrects for that double counting in its presentation of overall O&S costs.

5. Those amounts do not include costs for the MHS in accounts other than operation and support. For a detailed discussion of CBO’s methods of projecting costs for military health care as well as other individual components of DoD’s O&S, acquisition, and infrastructure budgets, see Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Obama Administration’s Final Future Years Defense Program (April 2017), www.cbo.gov/publication/52450.

6. For a more detailed discussion of CBO’s approach to analyzing costs for other O&M, see Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Obama Administration’s Final Future Years Defense Program (April 2017), pp. 30–31, www.cbo.gov/publication/52450.

7. For a more detailed discussion of CBO’s approach to analyzing growth in acquisition costs, see Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Obama Administration’s Final Future Years Defense Program (April 2017), pp. 47–50, www.cbo.gov/publication/52450.

This report was prepared at the request of the Chairman and Ranking Member of the Senate Committee on the Budget. In keeping with the Congressional Budget Office’s mandate to provide objective, impartial analysis, the report makes no recommendations.

David Arthur and F. Matthew Woodward coordinated the preparation of the report with guidance from David Mosher and Edward G. Keating. Elizabeth Bass, Michael Bennett, Eric J. Labs, and Adam Talaber contributed to the analysis. David Newman provided comments, and Edward G. Keating fact-checked the manuscript.

Mark Doms, Jeffrey Kling, and Robert Sunshine reviewed the report. Loretta Lettner edited it, and Jorge Salazar created the graphics and prepared the text for publication. The report is available at www.cbo.gov/publication/57541.

CBO seeks feedback to make its work as useful as possible. Please send comments to communications@cbo.gov.

Phillip L. Swagel

Director