At a Glance

Since its inception, the Congressional Budget Office has regularly published baseline projections of federal outlays, which, as required by law, reflect the assumption that current laws will generally remain unchanged. Those projections encompass the current year—the year in which the projections are made—and a projection period of 5 or (in the case of baseline projections since December 1995) 10 years in the future. In this report, CBO assesses the quality of the baseline projections of outlays it has made each spring from 1984 to 2021.

The report focuses on three fiscal years within each projection period: the budget year (typically the year beginning several months after the projections were made); the 6th year (counting the year that projections were made as the first year); and the 11th year. Comparing actual outlays with projected outlays is complicated by changes in law made after the projections were prepared. Therefore, for this analysis, CBO adjusted the original projections to reflect the estimated effects of legislation enacted after the projections were developed.

The results of CBO’s assessment are as follows:

- Total Outlays. CBO has tended to overestimate total outlays. Projections for the budget year have been more accurate than those for the 6th and 11th years for most categories of spending, primarily because changes in the economy and a variety of other factors are more difficult to anticipate over longer time horizons.

- Mandatory Outlays. The agency’s projections of total mandatory outlays for the budget year have generally been close to actual outlays, but projections for the 6th and 11th years have been less accurate. Projections of spending on Social Security have been the most accurate over all time horizons. Projections of spending on Medicare and Medicaid have been the least accurate of the 6th- and 11th-year projections. For the budget year, projections of other mandatory outlays (which consist of all mandatory spending other than that for Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) have been the least accurate.

- Discretionary Outlays. CBO’s projections of total discretionary outlays for the budget year, the 6th year, and the 11th year have generally been close to actual outlays. The major differences between the projections and actual outlays stem from misestimates of the rate at which funding was spent.

- Net Interest Outlays. The agency’s least accurate projections of federal outlays have been those of net interest outlays, which it has almost always overestimated. Those misestimates have been driven by CBO’s overestimates of interest rates.

- Comparison With Other Estimates. CBO’s and the Administration’s projections of outlays for the budget year have been similar in quality. (The Administration does not publish data about the accuracy of its projections beyond the budget year.) CBO’s projections, particularly of discretionary outlays, have been slightly more accurate than the Administration’s.

Notes

Unless this report indicates otherwise, all years referred to are federal fiscal years, which run from October 1 to September 30 and are designated by the calendar year in which they end.

Numbers in the text, tables, and figures may not add up to totals because of rounding.

Some of the figures in this report use shaded vertical bars to indicate periods of recession. (A recession extends from the peak of a business cycle to its trough.)

For the purposes of this analysis, outlays for the housing entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have been removed from the Congressional Budget Office’s projections and from actual amounts reported by the Treasury because CBO and the Administration account for those entities’ transactions differently.

CBO is the source of data for all figures in this report except the figure titled “Comparison of Average Errors in CBO’s and the Administration’s Budget-Year Projections of Outlays.” The data for that figure come from CBO and the Office of Management and Budget.

Supplemental data for this analysis are available on CBO’s website at www.cbo.gov/publication/58613#data.

Since its inception, the Congressional Budget Office has regularly published baseline projections of federal revenues and spending, which reflect the assumption that current laws will generally remain unchanged. In most years, the agency develops budget projections and an economic forecast for a report (The Budget and Economic Outlook) issued in the winter. That report is often followed by updated projections in the spring and summer.

Projections in that spring update (also known as the spring baseline) typically underlie the budget resolutions prepared by the House and Senate Budget Committees as well as CBO’s cost estimates for proposed legislation. Baseline projections can also be useful to policymakers seeking to identify and address budgetary trends that are likely to play out over the coming years if current laws remain in place. As part of the process of preparing its projections, CBO regularly assesses the quality of its past estimates of federal outlays, revenues, deficits, debt, and economic variables to refine its methods and improve the accuracy of its projections in the future.

This analysis updates CBO’s 2017 assessment of its baseline projections of outlays (available at www.cbo.gov/publication/53328). As did that earlier report, this one focuses on projections made for the second year (referred to as the budget year), which usually begins several months after a spring baseline is released, and for the 6th year (counting the year that projections were made as the first year).

But unlike that earlier report and previous editions of it, this one also evaluates projections made for the 11th year. Before 1995, CBO projected outlays for the current year and 5 years into the future; starting in December 1995, the agency extended its projections for 10 years beyond the current year. The first spring baseline with 11 years of projections was released in 1996 and is therefore the first one used in the analysis of 11th-year projections.

For more details about the specific projections included in this analysis for each category of spending, see Appendix A.

Assessing the Quality of CBO’s Projections

To assess the quality of its projections of outlays, CBO measured three of their characteristics: centeredness, accuracy, and dispersion.

- To measure centeredness, the agency calculated the average error—that is, the average of the annual projection errors. Those errors are expressed as a percentage, calculated by dividing the difference between projected outlays and actual outlays by the actual outlays; a positive number indicates an overestimate.

- The accuracy of projections was measured using the average absolute error and the root mean square error (RMSE). The average absolute error is the average of the errors without regard to whether they are overestimates or underestimates (the negative signs are removed from underestimates before averaging), so errors in different directions do not offset one another. The RMSE also measures the size of errors after removing the negative signs but, by squaring the errors, places a greater weight on larger deviations.

- To measure dispersion, CBO calculated the two-thirds spread of errors as the difference between the endpoints of the range of the errors after removing the one-sixth of errors furthest above the median and the one-sixth furthest below the median.

Because any comparison of actual outlays with projected outlays is complicated by changes in law made after the projections were developed, for this analysis CBO adjusted its original projections to reflect the estimated effects of legislation enacted after the projections were produced. Typically, those effects reflect costs or savings CBO estimated around the time the relevant legislation was enacted.

Thus, the analysis focuses on the remaining differences between projected and actual outlays—that is, it focuses on errors related either to CBO’s economic forecast or to other factors (referred to as technical factors), including misestimates of the effects of legislation, because the actual effects of legislation may well have differed from the estimated effects discussed above. In addition, for purposes of the analysis, the agency also removed outlays for the housing entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from its projections and from the actual amounts reported by the Treasury because CBO and the Administration account for those entities’ transactions differently.

Characteristics That CBO Measures to Assess the Quality of Its Projections

CBO uses measures of centeredness and accuracy when assessing potential changes to future baseline projections. The agency uses measures of dispersion to help illustrate the uncertainty of its projections.

Total Outlays

CBO has tended to overestimate outlays for the budget year, the 6th year, and the 11th year. In general, the accuracy of the agency’s projections tends to decrease over the projection period: Projections for the budget year have typically been more accurate than those for the 6th and 11th years. Some factors that account for the differences between CBO’s projections and actual outlays relate to the agency’s economic forecast. For example, forecasting interest rates has been particularly challenging, and errors in those forecasts affect the accuracy of projections of net interest outlays and spending on other programs. Other challenges include anticipating turning points in the economy and accurately reflecting the effects of recently enacted legislation.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Total Outlays

Percent

Because the 16 projections for the 11th year have all been overestimates, the average error and average absolute error are the same. Although the 11th-year projections have been less centered and less accurate than the 6th-year projections, those consistent overestimates are less dispersed, resulting in a smaller two-thirds spread of errors than the spread for 6th-year projections.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Total Outlays

Percent

CBO overestimated total outlays in its budget-year and 6th-year projections about 75 percent of the time. The 16 projections for the 11th year were the least accurate: Over half of them were more than 10 percent too high. Those errors were heavily influenced by large overestimates of net interest outlays.

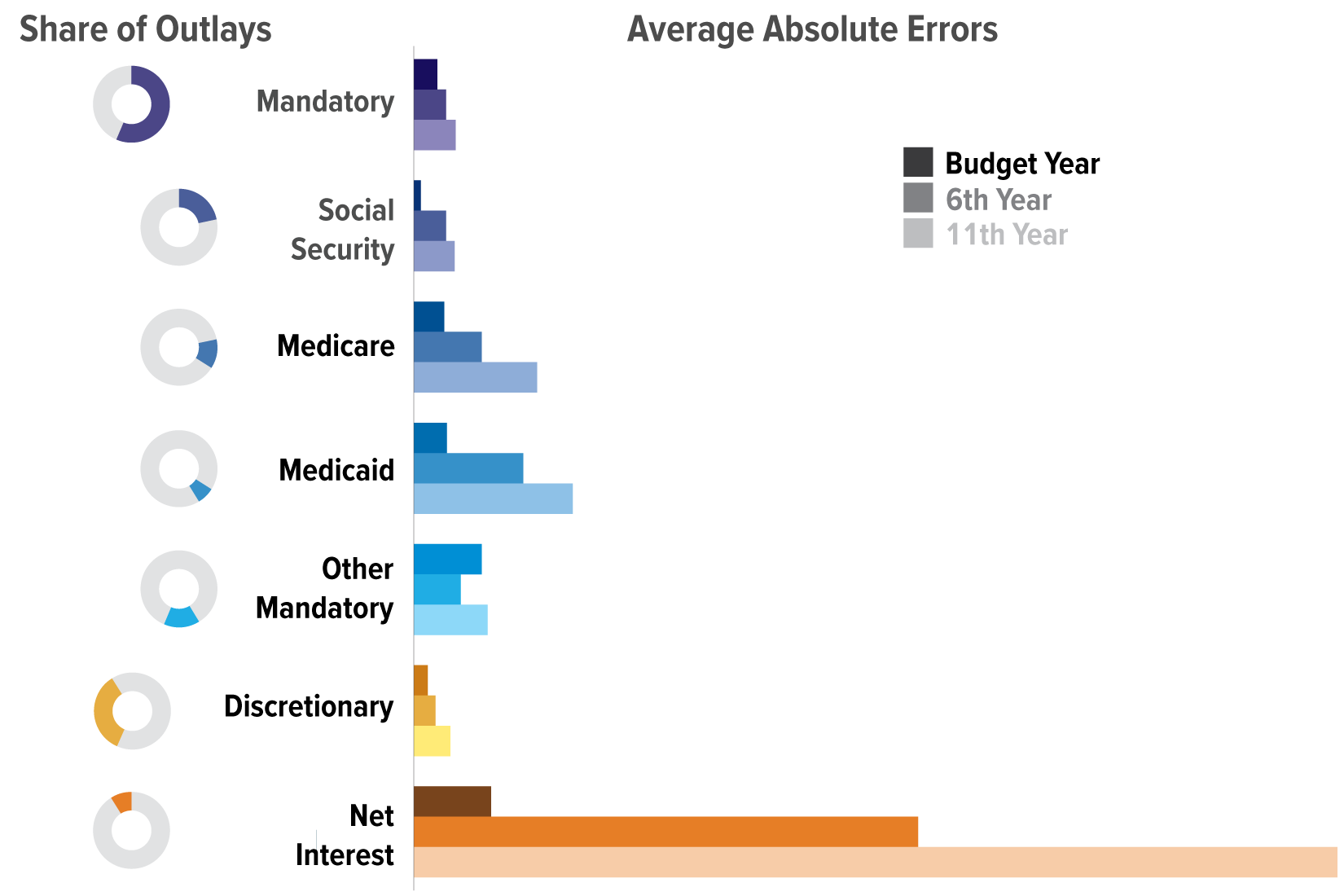

Major Categories of Outlays

Federal outlays can be divided into three broad categories: mandatory, discretionary, and net interest. Mandatory outlays (which averaged 56 percent of total outlays between 1993 and 2021) consist mostly of payments for benefit programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, but also include payments to other entities, such as businesses, nonprofit institutions, and state and local governments. Lawmakers largely determine funding for those programs by setting rules for eligibility, benefit formulas, and other parameters rather than by appropriating specific amounts each year. Discretionary outlays (which averaged 35 percent of total outlays between 1993 and 2021) result from the funding controlled by appropriation acts in which policymakers specify how much money can be obligated for certain government programs in specific years. Net interest outlays (which averaged 9 percent of total outlays between 1993 and 2021) consist of interest paid on Treasury securities and other interest that the government pays, minus the interest it collects from various sources.

Share of Total Outlays and Average Absolute Errors, by Category and Subcategory

Percent

Projections of discretionary outlays were the most accurate across most time horizons. Although net interest outlays constituted a relatively small percentage of total federal outlays over the 1993–2021 period, projections of those outlays were the least accurate.

Average Error for Each Projection Year, by Category and Subcategory of Outlay

Percent

Average errors for projections of net interest outlays have been larger than those for other major categories and subcategories of spending.

Mandatory Outlays

Mandatory outlays consist mostly of the federal government’s spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, which accounted for about 70 percent of mandatory outlays between 1993 and 2021. Other mandatory outlays include the refundable portions of the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit, and other tax credits, as well as spending on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, unemployment compensation, certain veterans’ programs, retirement benefits for federal employees, deposit insurance, and, more recently, assistance related to the coronavirus pandemic.

Context

The Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 requires CBO to develop baseline projections of spending for most mandatory programs under the assumption that current laws will generally remain unchanged. Thus, the agency’s projections of mandatory spending reflect changes in the economy, demographics, and other factors that it anticipates will occur under current law.

Mandatory Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

In the decade before 2020, mandatory spending averaged about 13 percent of GDP and 60 percent of total spending. Mandatory outlays increased significantly in 2020 and 2021 because of spending to address the pandemic. In 2021, mandatory outlays were 21 percent of GDP and accounted for 71 percent of total outlays.

Evaluation of Projections

Shorter-term estimates of mandatory spending have been more centered and accurate than longer-term estimates. For budget-year projections of such spending made for 1993 to 2021, the average error was about 2 percent. The average error was about 3 percent for the 6th-year projections and about 5 percent for the 11th-year projections.

Taking into account underestimates as well as overestimates, the average absolute error in projections of mandatory spending for the budget year was about 3 percent. Longer-term projections were less accurate; actual outlays differed from the 6th-year projections by roughly 4 percent and from the 11th-year projections by about 6 percent. The quality of projections varied among the subcategories of mandatory outlays: Projections of spending on Social Security were more centered and accurate than those of spending on Medicare and Medicaid.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Mandatory Outlays

Percent

Projections of mandatory spending for the 11th year have been almost entirely overestimates. In contrast, projections for the 6th year were both overestimates and underestimates. As a result, the 6th-year projections are slightly more dispersed than those for the 11th year.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Mandatory Outlays

Percent

CBO overestimated mandatory outlays in its budget-year projections about 70 percent of the time; 72 percent of the 6th-year projections were overestimates. Nearly 95 percent of the 11th-year projections were too high.

Social Security

The largest federal spending program, Social Security pays benefits to retired workers and their dependents and survivors through the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program and to disabled workers and their dependents through the Disability Insurance (DI) program. OASI constitutes nearly 90 percent of spending on Social Security.

Context

The main variables in projecting spending on Social Security are caseloads and benefit amounts. The size and stability of Social Security caseloads enable CBO to project spending on the program accurately in the near term; the number of beneficiaries who enter the program and those who exit constitute a relatively small percentage of the caseload each year. Thus, estimates of future caseloads are not particularly volatile in the near term. Projected average benefit amounts are based on forecasts of the growth in wages and of inflation. The initial amount of Social Security benefits that workers receive is based on their individual earnings histories (indexed to changes in average annual earnings for the U.S. workforce). Because the annual number of new entrants to the program is relatively small, the main determinant of the change in average benefits each year (and the source of most of the error in CBO’s projections of spending on Social Security) is the projected cost of living adjustment, or COLA, which is based on the annual increase, if any, in the consumer price index for urban wage earners and clerical workers.

Social Security Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Spending on Social Security increased from 4.5 percent of GDP in 1993 to 5.0 percent in 2021. Over that time, such spending generally averaged about 20 percent of total federal outlays.

Evaluation of Projections

CBO’s projections of spending on Social Security have been close to actual amounts; errors have mostly stemmed from misestimates of future COLAs. Those misestimates were larger for longer-term projections than for shorter-term ones and were both higher and lower than actual amounts, creating a larger spread of errors for the longer-term projections.

Overestimates of COLAs made for the 1990s were followed by underestimates made for the 2004–2015 period; overestimates have again been prevalent in more recent years. The largest underestimate for the 6th year was for 2009. In CBO’s initial 6th-year projection for 2009 (made in 2004), the estimated COLA was 2.2 percent, but the actual COLA for that year turned out to be 5.8 percent. In contrast, the largest overestimate for the 11th year was for 2021. In CBO’s initial 11th-year projection for 2021 (made in 2011), the estimated COLA was 2.3 percent, but the actual COLA for that year was 1.3 percent.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Social Security Outlays

Percent

Projections of spending on Social Security have been largely centered but with slightly more overestimates than underestimates. The projections have also been consistently accurate, although the longer-term projections have been less accurate and more dispersed than the shorter-term ones.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Social Security Outlays

Percent

Projected outlays for Social Security have been close to actual amounts but have been more likely to be overestimates: Two-thirds of the budget-year projections were slightly too high, and 56 percent of the 6th-year projections have been overestimates.

Medicare

The second-largest federal spending program, Medicare provides subsidized health insurance to people age 65 or older and to some people with disabilities. The program has three principal components: Part A (hospital insurance), Part B (medical insurance, which covers doctors’ services, outpatient care, and other medical services), and Part D (which covers outpatient prescription drugs).

Context

Spending on Medicare largely depends on the number of beneficiaries receiving coverage through the program, the amount of health care services those beneficiaries use, and the prices of those services. Like Social Security caseloads, Medicare caseloads are not particularly volatile, which enables CBO to project caseloads accurately. Because the prices and amount of health care services used have been comparatively more volatile, those two factors are the sources of most of the errors in CBO’s projections of spending on Medicare.

Medicare Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Spending on Medicare increased from 2 percent of GDP in 1993 to 3 percent in 2021. The share of total federal outlays devoted to Medicare rose from 9 percent in 1993 to 14 percent in 2019—before the pandemic-driven increase in total outlays in 2020 and 2021.

Evaluation of Projections

CBO has tended to overestimate spending on Medicare across all time horizons, in part because growth in spending has slowed unexpectedly at various times. Growth in Medicare spending slowed significantly from 1996 to 2002, and it took CBO several years to recognize that the change was more than a short-term deviation from past trends and to fully reflect the slowdown in its projections. That slowdown appears to have been caused by factors affecting beneficiaries’ demand for care and changes in providers’ behavior. A similar lag between a sustained slowdown and CBO’s recognizing and incorporating it into the agency’s projections of Medicare spending occurred around the time of the 2007–2009 recession.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Medicare Outlays

Percent

Projections of spending on Medicare for the budget year have tended to be overestimates. Longer-term projections have been less centered and less accurate and have been almost entirely overestimates. Because those consistent overestimates are less dispersed, the 11th-year projections have a smaller two-thirds spread of errors than the spread for 6th-year projections.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Medicare Outlays

Percent

One of the largest overestimates of Medicare outlays for most projection years occurred in 2021. That error was partly because payments that had been made to providers in 2020 in advance of expected health care claims were recouped more quickly than CBO expected. Also, as a result of the ongoing pandemic, Medicare experienced lower-than-expected usage of medical services in that year, so outlays were relatively low.

Medicaid

Medicaid, which is jointly financed by federal and state governments, is the main source of health insurance coverage for Americans who have very low income. States administer their Medicaid programs under federal guidelines that mandate a minimum set of services that must be provided to certain categories of low-income people. On average, the federal government pays for about 65 percent of the program’s costs, depending on the year. State Medicaid programs cover a comprehensive set of services, including hospital care (both inpatient and outpatient), physicians’ services, nursing home care, home health care, and certain additional services for children.

Context

Like Medicare spending, federal spending on Medicaid largely depends on the number of beneficiaries receiving coverage through the program, the amount of health care services those beneficiaries use, and the prices of those services. And as with the Medicare program, the prices and use of health care services in the Medicaid program have been volatile. But Medicaid caseloads have been more volatile than Medicare caseloads over the period covered by this analysis; significant differences between estimated Medicaid caseloads and actual caseloads are attributable to periods of strong economic growth as well as larger-than-expected increases in caseloads stemming from legislation such as the Affordable Care Act and legislation enacted to address the pandemic.

Medicaid Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Federal spending on Medicaid increased from 1 percent of GDP in 1993 to 2 percent in 2021. Over that time, the share of total outlays devoted to Medicaid grew from 5 percent to 8 percent.

Evaluation of Projections

CBO’s projections of spending on Medicaid for the budget year have generally been centered and close to actual values. However, longer-term projections of Medicaid outlays have been heavily influenced by volatile patterns of past growth. In the early 1990s, CBO expected the strong growth in spending that had characterized the previous decade to persist. But the growth in spending slowed abruptly beginning in 1994, in part because of legislation and because rapid economic growth held down enrollment in the program. In response to that period of lower growth, the agency lowered its projections of future spending growth for the program; but growth slowed even more than anticipated through the 2000s. For 2010 and later, CBO has consistently overestimated Medicaid outlays in its 6th- and 11th-year projections. Those overestimates stem from several factors, including slower-than-expected growth in spending for long-term care.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Medicaid Outlays

Percent

Budget-year projections of spending on Medicaid have been largely centered, whereas longer-term projections have tended to be overestimates. The projections have been accurate for the shorter term, but the longer-term projections have been less accurate and more dispersed.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Medicaid Outlays

Percent

For the budget-year, 6th-year, and 11th-year projections of Medicaid spending, the share of overestimates has been 66 percent, 84 percent, and 81 percent, respectively. The overestimates for the 11th year have been larger because the errors from the overestimated growth rate compounded over time.

Other Mandatory Outlays

In this analysis, the subcategory called other mandatory outlays encompasses all mandatory spending other than that on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. It includes outlays for retirement benefits of federal employees, certain veterans’ programs, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the refundable portion of certain tax credits (including the earned income tax credit, child tax credit, and other tax credits), some health care programs (other than Medicare and Medicaid), unemployment compensation, and deposit insurance, among other programs.

Context

Short-term projections of other mandatory outlays tend to be less accurate and more dispersed than short-term projections of other categories of outlays. That is largely because other mandatory spending includes most of the outlays for programs designed to address financial crises and, most recently, the pandemic. The budgetary effects of legislative responses to those crises have often been difficult to estimate because they involved the creation of new programs and were implemented during times of significant economic uncertainty. Any misestimates of the effects of those legislative responses are categorized as projection errors in this analysis. Misestimates of spending for countercyclical programs (that is, programs that tend to increase spending during economic downturns), such as unemployment compensation, also contribute to the projection errors. Outlays for countercyclical programs tend to be underestimated at the start of recessions and overestimated in periods of recovery.

Other Mandatory Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Other mandatory outlays have generally fluctuated between 2 percent and 3 percent of GDP. However, in 2020 and 2021, such outlays jumped to 11 percent of GDP, driven by an increase in pandemic-related spending. Before 2020, other mandatory outlays averaged about 14 percent of total outlays. In 2020 and 2021, they represented about 35 percent of total outlays.

Evaluation of Projections

Errors in projections of other mandatory outlays for the budget year have been heavily influenced by spending related to federal programs aimed at helping to resolve financial crises, such as the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). (See Appendix B for a more detailed discussion of how the accuracy of CBO’s projections is affected by credit programs such as the TARP.)

For 2020 and 2021, the budget-year projections of other mandatory outlays were more accurate than in previous recessions. The large increase in mandatory spending, stemming from legislation to address the pandemic, helped lower the percentage errors in those years, in part by significantly increasing actual outlays—the denominator used to calculate the errors. For example, from 2008 to 2009, amid the previous recession, other mandatory outlays increased by about $350 billion. From 2019 to 2020, such outlays increased by $1.6 trillion. The 2020 and 2021 budget-year projection errors were also smaller than the errors around previous recessions because some of the errors in the projections of outlays for certain pandemic-related programs offset one another.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Other Mandatory Outlays

Percent

Projections of other mandatory outlays for the budget year were overestimates, on average, whereas projections for the 11th year have been mostly underestimates.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Other Mandatory Outlays

Percent

Errors in projections of mandatory spending for the budget year are mostly attributable to estimates of spending on programs to help resolve financial crises. Misestimates of outlays for deposit insurance and for the TARP are the major sources of the large errors in the budget-year projections for 1993, 2010, and 2011.

Discretionary Outlays

Discretionary outlays result from funding controlled by appropriation acts in which policymakers specify how much money can be obligated for certain government programs in specific years. Appropriations fund a broad array of government activities, including defense, law enforcement, some education programs, and certain veterans’ health programs. They also fund the national park system, disaster relief, and foreign aid.

Context

Most of the differences between CBO’s projections of discretionary outlays and actual amounts tend to be legislative in nature and attributable to changes in funding provided each year in appropriation acts. After accounting for those legislative differences, the remaining differences between projections of discretionary outlays and actual amounts largely stem from the agency’s misestimating the rate at which funding would be spent.

Discretionary Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Discretionary outlays fell from 8 percent of GDP in 1993 to 7 percent in 2021. Over that time, discretionary outlays as a share of total outlays decreased from 38 percent to about 24 percent. (In 2019, just before the pandemic, discretionary outlays constituted 30 percent of federal outlays.)

Evaluation of Projections

For projections of discretionary outlays made for 1993 to 2005, the agency overestimated outlays for the budget year about 70 percent of the time, and the average error was less than 1 percent. CBO’s budget-year projections of discretionary outlays made since that time have all been overestimates (of about 2 percent, on average). One reason for the increase in the average error could be that full-year appropriations for the budget year have taken increasingly longer to finalize. From 1993 to 2005, full-year appropriations (appropriation bills that provide funding for an entire fiscal year) were finalized 65 days, on average, after the start of the fiscal year. That average increased to 123 days for the 2006–2021 period. Those longer delays in enacting final appropriations may have affected spending patterns in ways that CBO could not accurately anticipate.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Discretionary Outlays

Percent

Projections of discretionary outlays have tended to be overestimates largely stemming from overestimates of the rate at which funding would be spent. Because the same rates are often used to estimate outlays for individual accounts in each future year, errors tend to grow over time as misestimated rates affect more years. As a result, errors for the 6th and 11th years are typically larger than those for the budget year.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Discretionary Outlays

Percent

Projections of discretionary outlays have been largely accurate across all time horizons but have mostly been overestimates.

Defense

Discretionary spending is broadly divided into defense and nondefense spending. Defense discretionary spending includes spending on the military, atomic energy, and certain elements of homeland security. (A small portion of defense spending is mandatory and is included in the subcategory called other mandatory in this analysis.) Before 1998, CBO did not consistently report separate projections of the two categories; it reported only total discretionary spending. As a result, CBO does not have the historical data needed to distinguish between defense and nondefense spending in projections made before 1998.

Context

Lawmakers appropriate funding each year for the majority of defense activities. (A few programs receive multiyear appropriations.) Depending on the activity or program, federal spending that arises from that budget authority can occur quickly (to pay salaries, for example) or slowly (to pay for long-term research and construction). Thus, defense discretionary outlays recorded each year come from prior appropriations as well as new budget authority. To estimate the amount of outlays that would result from projected levels of defense discretionary funding, CBO typically evaluates factors such as the purpose of the funding, the historical rate at which budget authority has been obligated and spent, and the amount of outstanding budget authority available from previous years’ appropriations.

Defense Discretionary Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Discretionary outlays for defense averaged 3.6 percent of GDP from 1998 to 2021. (During that period, they peaked at 4.6 percent of GDP in 2010 because of spending on military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq.) The share of total outlays devoted to defense fell slightly from 1998 to 2019. The share was even smaller in 2020 and 2021 because of the large increase in mandatory outlays related to the pandemic.

Evaluation of Projections

CBO’s projections of defense discretionary outlays have generally been accurate. Over 40 percent of the budget-year projections have been within 1 percent of actual amounts. Of the categories analyzed in this report, only projections of spending on Social Security have been more centered for the budget year and only projections of Other Mandatory outlays have been more centered for the 6th year. Projections of defense discretionary outlays have been the most centered of all the categories of outlays for the 11th year.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Defense Discretionary Outlays

Percent

Projections of defense discretionary outlays have been largely accurate across all time horizons but have mostly been overestimates.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Defense Discretionary Outlays

Percent

Misestimates of defense discretionary outlays have generally been small, averaging about 1 percent for the budget year and about 2 percent for the 6th year. They stem mostly from overestimates of the rate at which funding would be spent. Since those effects tend to grow over time as more years are affected, the misestimates are larger for the 11th-year projections, averaging about 3 percent.

Nondefense

Nondefense discretionary spending includes outlays for education, transportation, public health, and a range of other programs. Before 1998, CBO did not consistently make separate projections of defense and nondefense spending; the agency projected only total discretionary spending. As a result, CBO does not have the necessary historical data to distinguish between defense and nondefense spending in projections made before 1998.

Context

As they do for defense discretionary spending, lawmakers appropriate funding each year for the majority of nondefense discretionary activities. (A few programs receive multiyear appropriations.) When projecting nondefense discretionary outlays, CBO typically evaluates factors such as the purpose of the funding, the historical rate at which budget authority has been obligated and spent, and the amount of outstanding budget authority available from previous years’ appropriations—just as it does to project defense discretionary outlays.

Nondefense Discretionary Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Since 1998, nondefense discretionary outlays have averaged about 4 percent of GDP. Measured as a percentage of total federal outlays, nondefense discretionary outlays declined from 17 percent in in 1998 to roughly 15 percent in 2019, and from 14 percent in 2020 to 13 percent in 2021.

Evaluation of Projections

CBO’s projections of nondefense discretionary outlays have been less centered and less accurate than projections of defense discretionary outlays. Although those misestimates have generally been small, the consistent overestimates of nondefense outlays drive the consistent overestimates of total discretionary outlays.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Nondefense Discretionary Outlays

Percent

Projections of nondefense discretionary outlays have almost always been overestimates.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Nondefense Discretionary Outlays

Percent

For the budget-year, 6th-year, and 11th-year projections of nondefense discretionary outlays, the share of overestimates has been 87 percent, 95 percent, and 100 percent, respectively. Those overestimates stem from expectations that funding would be spent more rapidly than it was. For all three projection periods, overestimates have increased over the past several years.

Net Interest Outlays

Net interest outlays include interest paid on Treasury securities and other interest that the government pays (for late refunds issued by the Internal Revenue Service, for example), minus the interest that it collects from various sources (primarily from specialized financing accounts, which track the cash flows of credit programs like the federal student loan programs).

Context

Net interest outlays are mainly determined by the size and composition of the government’s debt and by market interest rates. Errors in CBO’s projections of such outlays have stemmed from misestimates of interest rates (and, to a lesser degree, of inflation). Over the 1993–2021 period, the agency substantially overestimated interest rates. For example, in March 2011, CBO projected that interest rates on 10-year Treasury notes would average 4.8 percent over the 2011–2021 period and that net interest outlays would total (after adjusting for subsequent legislation) more than $940 billion in 2021. Actual interest rates for the 10-year Treasury notes averaged 2.1 percent, and net interest outlays in 2021 were about $350 billion.

Net Interest Outlays and Total Outlays

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Despite rising debt, net interest outlays fell from 3 percent of GDP in 1993 to 2 percent in 2021 because interest rates generally declined during that time. As a share of total outlays, net interest outlays declined from 14 percent in 1993 to 8 percent in 2019—and they fell to 5 percent of total outlays in 2020 and 2021, when other types of outlays increased as a result of pandemic-related spending.

Evaluation of Projections

CBO overestimated net interest outlays in most of the years examined in this report. Moreover, the largest percentage errors have been in projections of net interest outlays. Especially for years beyond the first few years of the baseline, errors in the projections of net interest outlays have been much larger than those in any other category or subcategory of outlay.

Measures of the Quality of CBO’s Projections of Net Interest Outlays

Percent

Projections of net interest outlays have been substantially less centered, less accurate, and more dispersed than projections of other types of outlays. Because projections for the 11th year have been exclusively overestimates, the average error and average absolute error for the 11th year are the same.

Errors in CBO’s Projections of Net Interest Outlays

Percent

Because the overestimates of interest rates were larger for longer-term projections, the projections for the 6th and 11th years were less accurate than those for the budget year. Of all the categories of outlays evaluated in this report, CBO’s 11th-year projections of net interest outlays were the source of the largest percentage differences between projected and actual outlays.

Interest Rates

CBO (and other forecasters) did not anticipate the extent or persistence of the decline in interest rates that occurred from the early 1980s to 2021. Thus, the agency (and other forecasters) tended to make sizable overestimates of both short- and long-term interest rates, particularly since the early 2000s.

The Persistent Decline in Interest Rates

Percent

Interest rates have trended downward since the early 1980s. That decline persists even after taking into account the effects of the reduction in inflation. Recent research has identified several possible contributors to the decline: the aging of the population, increased income inequality, a trend toward slower output growth, and increased saving among emerging market economies.

Errors in CBO’s Forecasts of Interest Rates

Percentage Points

Overestimates of interest rates are the primary reason for CBO’s overestimates of net interest outlays.

Uncertainty

To illustrate the uncertainty of its projections of outlays, CBO typically overlays the two-thirds spread of errors associated with total outlays for projections made since 1984 onto its projection of outlays for the current year and the next five years. The comparatively larger errors in projections of Medicare, Medicaid, and net interest outlays mean that there is greater uncertainty in those projections than in projections of other categories of outlays. Those three categories accounted for 29 percent of total federal outlays from 1992 to 2021. In CBO’s February 2023 baseline budget projections, outlays for those categories are projected to grow from 33 percent of total federal outlays in 2023 to 37 percent in 2028. As Medicare, Medicaid, and net interest outlays make up an increasing share of total outlays, the uncertainty of CBO’s baseline projections of total outlays will increase.

Uncertainty of CBO’s Projections of Total Outlays

Trillions of Dollars

On the basis of historical errors associated with total outlays, the two-thirds spread of errors for CBO’s February 2023 projection of outlays in 2028 is $0.9 trillion.

Comparison With the Administration’s Projections

In addition to assessing the quality of its own projections of spending, CBO compared its budget-year projections with those released by the Administration. In the Analytical Perspectives volume that it publishes annually along with the budget, the Administration provides information about differences between its budget-year baseline projections and actual outlays for broad categories of spending; however, it does not generally provide details for specific programs. As a result, CBO could only compare the projections of total outlays and those of the three main categories of spending—mandatory, discretionary, and net outlays for interest. The Administration has not published detailed information on the accuracy of its projections beyond the budget year, so CBO could not compare the Administration’s 6th-year or 11th-year projections with its own.

Comparison of Average Errors in CBO’s and the Administration’s Budget-Year Projections of Outlays

Percent

The Administration’s budget-year projections of total outlays and of mandatory, discretionary, and net interest outlays have been close to CBO’s projections in most years since 1993. On average, CBO’s projections have been slightly more centered. Since 2006, average errors have decreased in both CBO’s and the Administration’s projections of mandatory outlays. Errors in projections of discretionary and net interest outlays have increased.

Appendix ADetails About CBO’s Method for Assessing Its Projections of Outlays

To assess its past projections of outlays, the Congressional Budget Office compared them with actual amounts recorded in the budget and attempted to determine the sources of any differences between the two. Because the agency intentionally does not incorporate the effects of possible legislative changes into its baseline projections, this report focuses on the differences between projected and actual outlays that result from economic or technical factors only.

To adjust the projections of outlays to include the effects of subsequent legislation, this analysis relies on the legislative changes to CBO’s budget projections that are described in the annual Budget and Economic Outlook and updates to that report that are published each year. Typically, those changes reflect the agency’s estimates of costs or savings around the time the relevant legislation was enacted but sometimes include subsequent updates. The actual budgetary effects of legislation may have differed from those estimates. If so, those differences are reflected in this analysis as errors in the baseline projections.

For the purposes of this analysis, the agency removed outlays for the housing entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from its projections and the actual amounts reported by the Treasury Department because CBO and the Administration account for those entities’ transactions differently.

Categories of Outlays and Time Line of Projections Examined in This Analysis

Although CBO has regularly published baseline budget projections since its inception, the number of years covered by those projections has changed over time. Between March 1984 (the earliest year included in this evaluation) and April 1995, the agency’s projections typically covered the current year and the next 5 fiscal years. Since that time, the agency’s baseline projections have covered the current fiscal year and the next 10 fiscal years. Additionally, on the basis of the availability of data, the projections included in this analysis vary by category of outlay and by projection period (see Table A-1).

Table A-1.

Years and Number of Projections Included in This Analysis, by Category of Outlay

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/58613#data.

For example, in March 2020, CBO released projections of outlays for fiscal year 2020 (the current year), fiscal year 2021 (the budget year), and for each of the next nine years. The Department of the Treasury reports the actual amounts of outlays for each year in October, shortly after the end of the fiscal year (see Figure A-1). Those preliminary amounts are finalized when the Administration releases its projections the following spring. (Those actual amounts are subject to later revisions, which, if made, are typically small.)

Figure A-1.

Sample Time Line for Measuring Errors in CBO’s Projections of Outlays for the Budget Year

Data source: Congressional Budget Office.

Dates for the budget-year projection for outlays in 2021 (the most recent examined in this study) are used in this time line for illustrative purposes. The time lines for measuring errors in all budget-year projections of outlays are similar, although CBO does not release such projections on this schedule each year, and the President’s budget is not always released in February.

Adjusting for Legislation

Because any comparison of actual outlays with projected outlays is complicated by changes in law made after the projections were prepared, for this analysis CBO adjusted the original projections to reflect the estimated effects of legislation enacted after the projections were produced. Those estimated effects of legislation are typically the legislative changes reported in CBO’s Budget and Economic Outlook. (See Table A-2 for an example of how projections are adjusted.)

Table A-2.

How CBO Adjusts Its Budget-Year Projections of Total Outlays to Compare Them With Actual Spending: An Example Using the March 2020 Projections for 2021

Billions of Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/58613#data.

The periods identified above correspond to the intervals between successive baseline projections, which CBO typically publishes each winter, early spring, and summer.

a. CBO did not estimate any legislative effects for fiscal year 2021 between July 2021 and the end of the fiscal year.

Removing the estimated effects of legislation helps concentrate the analysis on the remaining differences between projected and actual outlays—that is, on errors related either to CBO’s economic forecast or to other factors (referred to as technical factors). However, the actual effects of legislation may well have differed from the estimated effects that were removed from the baseline; thus, those errors in estimated legislative effects appear as misestimates in the adjusted baseline used for this analysis. For most categories of outlays, the estimated effects of legislation are larger than the projection errors (see Figure A-2).

Figure A-2.

Estimated Effects of Legislative Changes and Total Projection Errors in the 6th Year, by Category of Outlay

Trillions of Dollars

The largest differences between CBO’s projections of mandatory and discretionary outlays and the actual outlays stem from legislative changes rather than from projection errors (that is, the errors attributable to economic or technical factors). For net interest outlays, total projection errors are nearly three times as large as the effects of legislative changes; most of that total stems from overestimating interest rates.

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/58613#data.

Mandatory outlays consist of the federal government’s spending on benefit programs and certain other payments to people, businesses, nonprofit institutions, and state and local governments. They include outlays for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, student loans, certain refundable tax credits, and other programs that generally are governed by statute rather than by specific annual appropriations.

Discretionary outlays comprise spending for defense and nondefense activities. Defense discretionary spending consists of funding for various activities related to national defense, including military personnel, operations, maintenance, procurement, research and development, facilities, and defense-related nuclear programs. Nondefense discretionary spending comprises funding for education and training, transportation, certain veterans’ benefits, law enforcement, national parks, disaster relief, and foreign aid, among other activities.

Net interest outlays include interest paid on Treasury securities and other interest that the government pays, minus the interest that it collects from various sources.

Excluding Outlays Associated With Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

CBO also adjusted its baseline projections and the actual amounts reported to remove outlays related to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two entities that help to finance the majority of mortgages in the United States. CBO accounts for the activities of those entities differently than the Administration does in the budget or the Treasury does in its reports, so the projections and the reported amounts are not comparable.

Since 2008, when the federal government placed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into conservatorship, CBO and the House and Senate Budget Committees have considered those institutions’ activities as governmental. Thus, in CBO’s view, transactions between Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the Treasury should be considered intragovernmental. The Administration, by contrast, considers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to be outside the federal government for budgetary purposes and thus records their transactions with the Treasury as increases or decreases in federal outlays. Because the accounting for those two concepts is entirely different, comparing CBO’s estimates with the amounts reported by the Treasury would not contribute to a meaningful assessment of the centeredness or accuracy of CBO’s projections of outlays.

Appendix BThe Effect of Credit Subsidy Reestimates on Errors in CBO’s Projections of Other Mandatory Outlays

Although most federal activities are recorded in the budget on a cash basis, federal credit programs—loans and loan guarantees made by the federal government—are recorded differently, using procedures established by the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA). As a result of those procedures, the actual outlays recorded each year are affected by revisions, collectively labeled credit subsidy reestimates, made by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) on the basis of its updated assessment of the costs of or savings from outstanding loans. Because the Congressional Budget Office does not attempt to estimate the amount of the Administration’s revisions each year, the revisions are a source of error in CBO’s projections.

The federal government supports some private activities by providing credit assistance to individuals and businesses. That assistance is provided through direct loans and guarantees of loans made by private financial institutions. When developing its baseline projections, CBO estimates a subsidy rate for each loan program, typically on the basis of projections of future loan activity. The subsidy rate is the cost of the program divided by the amount of funds disbursed. A positive subsidy rate indicates a cost to the government; a negative rate indicates budgetary savings.

Estimates of the payments and receipts of a credit program, and the consequent net costs, change over time as economic conditions evolve and government agencies gain more experience with their loans and loan guarantees. As directed by FCRA, OMB reviews the subsidy costs of federal loans and loan guarantees each year and records any credit subsidy reestimates as increases or decreases in budgetary outlays. Typically, CBO does not include such reestimates in its baseline projections until OMB publishes the amounts of reestimates it will formally record as outlays for each affected program. In this analysis, credit subsidy reestimates appear in the subcategory of outlay called other mandatory outlays.

In most years since 1993, the amount of credit subsidy reestimates has been relatively small (see Figure B-1). During that time, net reestimates have exceeded $15 billion (as either a budgetary cost or savings) in only four years: 2010, 2011, 2017, and 2020. In 2010 and 2011, there were large downward reestimates of the cost of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Conversely, in 2017 and 2020, there were large upward reestimates related to the cost of past student loans.

Figure B-1.

Total Credit Subsidy Reestimates, 1993 to 2021

Billions of Dollars

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/58613#data.

A credit subsidy reestimate is a change in the estimated cost of an outstanding group of loans arising from changes in assumptions about those loans’ future cash flows. The Office of Management and Budget makes credit subsidy reestimates periodically each year on the basis of changes in economic assumptions (concerning interest rates, for example) and in technical assumptions (for default rates, for example).

Because the amount of credit subsidy reestimates in most years has been relatively small, their effect on errors in CBO’s projections of other mandatory outlays has also been small (see Figure B-2). The largest exceptions are the reestimates for the TARP in 2010 and 2011, which significantly affected the size of errors in those years. Because credit subsidy reestimates affect outlays in the year in which they are recorded in the budget, for credit programs there is a mismatch between when the estimate was originally made and when estimating errors appear in CBO’s track record. For the TARP, CBO’s original estimate was made in 2009, when most of the program’s activity took place. The error associated with that estimate appeared in 2010 and 2011, when the credit subsidy reestimates were recorded in the budget.

Figure B-2.

Errors in CBO’s Budget-Year Projections of Other Mandatory Outlays, With and Without Credit Subsidy Reestimates, 1993 to 2021

Percent

Data source: Congressional Budget Office. See www.cbo.gov/publication/58613#data.

Other mandatory outlays consist of all mandatory spending other than that for Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

A credit subsidy reestimate is a change in the estimated cost of an outstanding group of loans arising from changes in assumptions about those loans’ future cash flows. The Office of Management and Budget makes credit subsidy reestimates periodically each year on the basis of changes in economic assumptions (concerning interest rates, for example) and in technical assumptions (for default rates, for example).

About This Document

Each winter, the Congressional Budget Office issues a report on the state of the budget and the economy, which is often updated in the spring and summer. The first set of updated projections typically serves as the basis for CBO’s estimates of legislation as well as the Congress’s budget resolution for the year to come. This document provides background information on the centeredness, accuracy, and dispersion of the projections of outlays included in those reports. In keeping with CBO’s mandate to provide objective, impartial analysis, the report makes no recommendations.

Aaron Feinstein wrote the report with guidance from Christina Hawley Anthony, Theresa Gullo, Leo Lex (formerly of CBO), and Sam Papenfuss. Ron Gecan and James Williamson offered comments. Meredith Decker, Ann E. Futrell, Kevin Perese, Justin Riordan, and Olivia Yang fact-checked the report. Kevin Perese reviewed and edited computer code used in the analysis and released as part of the report’s supplemental data.

Mark Doms, Jeffrey Kling, and Robert Sunshine reviewed the report. Scott Craver edited it, and R. L. Rebach created the graphics and prepared the text for publication. The report is available at www.cbo.gov/publication/58613.

CBO seeks feedback to make its work as useful as possible. Please send comments to communications@cbo.gov.

Phillip L. Swagel

Director

April 2023