The federal government’s net outlays for mandatory health care programs, combined with the subsidies for health care that are conveyed through reductions in federal taxes, exceeded $1.0 trillion in fiscal year 2013, CBO estimates. Net outlays for Medicare and Medicaid, the two largest federal health care programs, totaled an estimated $760 billion, roughly one-quarter of all federal spending in 2013. Other mandatory health care programs include the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the Federal Employees Health Benefits program for civilian retirees, and the TRICARE for Life program for military retirees. In addition, the federal tax code gives preferential treatment to payments for health insurance and health care, primarily through the exclusion of premiums for employment-based health insurance from income and payroll taxes. CBO estimates that the tax expenditure for that exclusion (accounting for income and payroll taxes together) was about $250 billion in 2013. The federal government also supports many health programs that are funded through annual discretionary appropriations: Taken together, funding for public health activities, health and health care research initiatives, health care programs for veterans, and certain other health-related activities totaled about $115 billion in 2013. (In addition, the federal government makes contributions for health insurance premiums for active civilian and military workers, but that funding is part of each agency’s budget and is not included in that figure.)

[collapsed title="…read more" class="read-more"] Under current law, federal budgetary costs related to health will increase considerably starting in 2014, as some people become newly eligible for Medicaid and others qualify for tax subsidies to purchase coverage through new health insurance exchanges. Policy changes relating to health could reduce federal deficits by lowering outlays for mandatory health care programs and by limiting tax preferences for health care. Reductions in discretionary spending on health programs would reduce total appropriations if the statutory caps set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 were reduced as well, or if appropriations were provided at levels below those caps.

[/collapsed]Trends in Spending and Revenues Related to Health

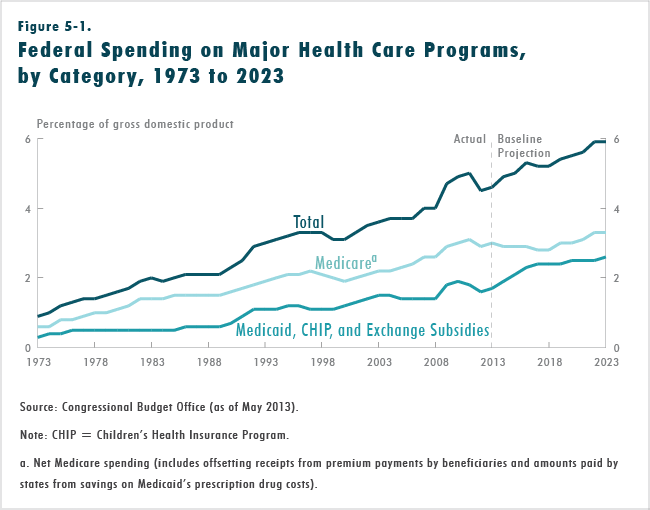

Spending for Medicare and Medicaid has grown quickly in recent decades, in part because of rising enrollment. Rising costs per enrollee also have driven spending growth in those programs—much like growth in private spending for health care. In 1975, a decade after the enactment of legislation creating the Medicare and Medicaid programs, federal spending on those programs, net of offsetting receipts, accounted for 1.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). That share rose to 2.0 percent of GDP by 1985 and has more than doubled since then, as net federal spending for the two programs grew to 4.6 percent of GDP in 2013, by CBO’s estimates. Between 1985 and 2013, the share of the population enrolled in Medicare rose from 13 percent to 16 percent, and average annual enrollment in Medicaid rose from 8 percent to 18 percent of the population. Including the smaller CHIP (which was established in 1997), 20 percent of the population was enrolled in either Medicaid or CHIP, on average, in 2013, according to CBO’s estimates.

Per capita spending for health care in this country has been rising in recent decades. A key reason has been the emergence, adoption, and widespread diffusion of new medical technologies and services. Other factors contributing to the growth of health care spending include increases in personal income and the expanded scope of health insurance coverage. Altogether, health care spending per person has expanded more rapidly than the economy for a number of years, although the rate of increase in health care spending has slowed recently.

The tax expenditure stemming from the exclusion from taxable income of employers’ contributions for health care and workers’ premiums for health insurance and long-term-care insurance—described in this report as the exclusion for employment-based health insurance—also depends on health care spending per person. That tax expenditure equaled 1.5 percent of GDP in 2013, CBO estimates.

Discretionary spending related to health also has grown significantly in recent decades. From 1973 to 1998, it rose at an average annual rate of about 7 percent, and that rate increased to 10 percent between 1998 and 2004. Since then, health-related discretionary spending has risen more slowly overall—at an average annual rate of about 5 percent—although spending in different program areas has grown at markedly different rates. For example, from 2004 to 2012, outlays for veterans’ health care rose at an average annual rate of 8 percent, whereas spending for health research and training (mostly by the National Institutes of Health) grew by an average of about 3 percent per year.

Over the next decade, the government’s health care programs will be a continuing source of budgetary pressure—primarily because of a sharp increase in the numbers of beneficiaries enrolled in those programs but also because of ongoing growth in health care costs per beneficiary. Assuming that current laws governing those programs generally do not change, net federal spending for Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and subsidies for premiums and cost sharing in the health insurance exchanges is projected by CBO to reach 5.9 percent of GDP in 2023, compared with 4.6 percent in 2013 (see Figure 5-1). By comparison, outlays for Social Security are projected to be 5.3 percent of GDP in 2023. The tax expenditure for employment-based insurance (including income and payroll taxes) will remain close to 1.5 percent of GDP during the coming decade, CBO projects. Although health care costs per person are expected to continue to grow faster than the economy, which will tend to push up the tax expenditure relative to GDP, an excise tax on high-cost employment-based plans (set to begin in 2018) will work in the opposite direction.

The projected rise in the number of beneficiaries of federal health care programs has two main causes. First is the aging of the population—particularly the retirement of the baby-boom generation—which, over the next 10 years, will result in an increase of about one-third in the number of people who receive benefits from Medicare. Second is the expansion of federal support for health insurance under current law, which will boost the number of Medicaid recipients and make other people eligible for subsidies as they purchase health insurance through exchanges. Despite the significant expansion of federal support for health care for lower-income people over the next 10 years, only about one-fifth of federal spending for the major health care programs in 2023 will finance care for able-bodied, nonelderly people. CBO projects that roughly another one-fifth will fund care for people who are blind or disabled, and about three-fifths will go toward care for people who are 65 or older.

Projecting the growth of per capita spending for health care is particularly challenging in light of the recent slowdown in that growth. A key question is the extent to which the slowdown can be attributed to temporary factors such as the recession and the slow recovery, and the extent to which it instead reflects more enduring developments in the health care system. In CBO’s judgment, per capita health care spending will continue to grow slowly over the next decade. Accordingly, during the past few years, CBO has substantially reduced its projections of spending on Medicare and Medicaid for the coming decade and slightly lowered its estimate of the underlying rate of growth for health care spending per person for the country as a whole.

Methodology Underlying Estimates Related to Health

CBO and the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated the budgetary effects of the options in this chapter related to mandatory spending and revenues relative to CBO’s projections of spending and revenues if current laws generally remained unchanged. Those baseline projections incorporate estimates of future economic conditions, demographic trends, and other developments that reflect the experience of the past several decades and the effects of broad, ongoing changes to the nation’s health care and health insurance systems that are occurring under current law. In particular, the projections incorporate the effects of several provisions of law that will constrain the rates that Medicare pays health care providers, among them the following:

- Payment rates for physicians’ services, which are governed by the sustainable growth rate mechanism, are set to decline by about 24 percent in January 2014. CBO projects that, if current law remains in place, those payment rates will increase by small amounts in most subsequent years but will remain below 2013 levels throughout the 2014–2023 period.

- Annual updates to payment rates for health care providers other than physicians in Medicare’s fee-forservice program will be restrained by a number of provisions in current law. Other provisions will slow the growth in payment rates for beneficiaries enrolled in the private insurance plans that provide Medicare benefits.

- Most Medicare payments to providers for services furnished from April 2013 to March 2022 will be reduced as a result of the automatic procedures (known as sequestration, or the cancellation of funding) in the Budget Control Act.

Savings for options related to discretionary spending were estimated relative to CBO’s baseline projections for such programs, as described in the chapter on discretionary spending options.

Options in This Chapter

Most of the 16 options in this chapter would either decrease federal spending on health programs or increase revenues (or equivalently, reduce tax expenditures) as a result of changes in tax provisions related to health care. Some options would result in a reallocation of health care spending—from the federal government to businesses, households, or state governments, for example—and most would give parties other than the federal government stronger incentives to control costs while exposing them to more financial risk.

Eleven of the options are similar in scope to others in this report and in previous volumes. For each of those options, the text provides background information, describes the possible policy change or changes, presents the estimated effects on spending or revenues, and summarizes arguments for and against the changes.

The other five options address broad approaches to changing federal health care policy, all of which would offer lawmakers a variety of alternative ways to alter current law. For each of those options, the amount of federal savings and the consequences for stakeholders—beneficiaries, employers, health care providers, insurers, and states—would depend crucially on which of the alternatives were chosen.The five broad approaches are the following:

- Impose caps on federal spending for Medicaid,

- Convert Medicare to a premium support system,

- Change the cost-sharing rules for Medicare and restrict medigap insurance,

- Bundle Medicare’s payments to health care providers, and

- Reduce tax preferences for employment-based health insurance.

Another option for reducing federal spending on health care would be to repeal the provisions of the Affordable Care Act that expand Medicaid coverage and provide subsidies for health insurance purchased through exchanges, along with other related changes in law. That option is not included in this volume, but the budgetary savings from repealing those coverage provisions would be close to their net costs, which CBO and JCT estimated most recently to be about $1.4 trillion over the 2014–2023 period. In addition to the budgetary effects, the repeal of those provisions would greatly increase the number of people who would be uninsured over the next decades compared with the number under current law, and would have many other effects as well. Repeal of the entire law, which includes provisions that will reduce other spending and boost revenues, would, on net, increase budget deficits, CBO and JCT estimate.

In addition to their effects on the federal budget, the 16 options examined in this chapter would have a variety of other consequences. Some options are designed to affect people’s behavior as they participate in the health care system. Some focus on influencing the actions of health care providers or health care plans. Still others would change the ways the government paid providers or alter the role of the federal government or the states in paying for health care services. One option would have major consequences for health researchers around the country, and one would promote better health in the population—along with increasing federal revenues—through an increase in the excise tax on cigarettes. A number of the options could shift the sources or types of health insurance coverage or cause different types of health care to be sought and delivered. Whether that care was delivered more efficiently or was more appropriate or of higher quality than it would be otherwise would hinge on the responses of those affected.

CBO and JCT estimated the budgetary impact of each option independently of the others, without consideration of potential interactions among them. The agencies accounted for the time that would be required to implement each policy and for the time needed for the effects to fully phase in. If an option would be straightforward and could be implemented fairly rapidly, it was assumed to take effect in 2014 or 2015 (depending on the specific features of the option). If a policy would take longer to implement, then few effects, if any, on federal spending or revenues were estimated for the early part of the 10-year projection period.

Subsequent cost estimates by CBO or revenue estimates by JCT for legislative proposals that resemble the options in this chapter could differ from the estimates shown here because the policy proposals forming the basis of those later estimates might not precisely match the options. In addition, although the estimates in this chapter rely on CBO’s and JCT’s current analysis of and judgment about the responses of individuals, businesses, and health care providers to changes in the health care system, more detailed future analyses—or the availability of new data or research results—could result in different estimates. Moreover, the baseline budget projections against which such proposals ultimately would be measured might differ because of legislative or administrative actions or because of other changes in CBO’s estimates. Finally, in some cases, CBO has not yet developed specific estimates of secondary impacts for some options that would primarily affect mandatory or discretionary spending or revenues but that also could have other, less direct, effects on the budget.